EUROPE AGAINST THE CURRENT

article originally writen for the Dutch journal de Gids (mei 1990) by

Tjebbe van Tijen

"For year on end, Europe, the birthplace of the nation-states with their international marketed 'national' cultures has been the locus of a different kind of international cultural exchange

-that ignores the restrictions of nationality

-does not bother about power blocks

-bursts accepted

forms."

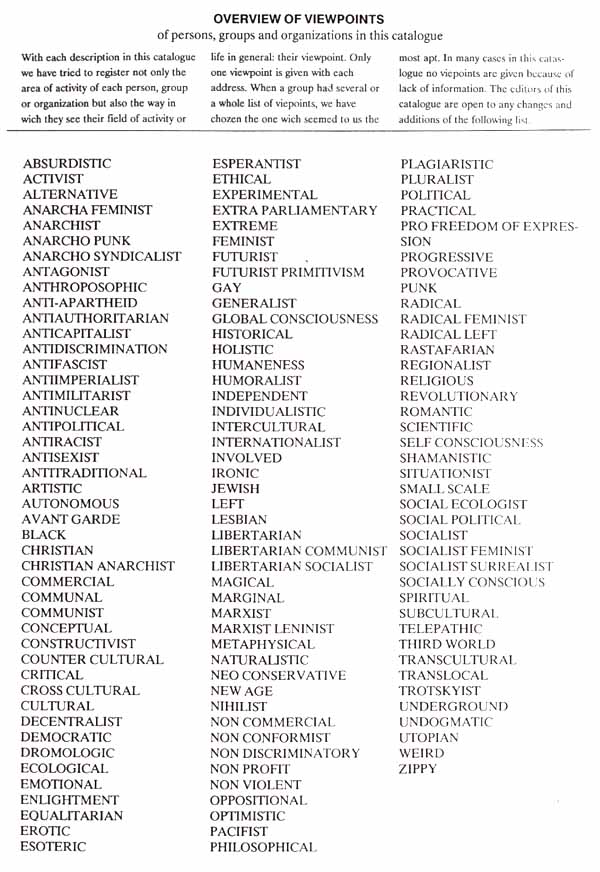

Opening words of a manifesto circulated during the years 1987-1988 all

over Europe in ten different languages. A call to persons, groups and

bodies considering themselves 'alternative', 'independent', 'radical'

to take part in the first European self-presentation of publishers, distributors

and others involved in the circulation of 'information carriers'.

Products to be on show: posters, books, periodicals, records, cassettes,

film, video, watchwords: break down the usual barriers separating disciplines

such as visual arts, music, theatre, film; stimulate multidisciplinary

approaches; multiplication of multiple themes. Political, minority, cultural,

emancipatory issues were to be shown as interconnected.

The manifesto does not end with the usual call to unite around the common

flag but encourages pluriformity: "the presentation of a wide spectrum

of views".

![]() click green bullet to jump to the full text of the manifesto as issued

in 1988

click green bullet to jump to the full text of the manifesto as issued

in 1988

![]() click red bullet for link to archives of the Foundation Europe Against

The Current at the International Institute of Social History

click red bullet for link to archives of the Foundation Europe Against

The Current at the International Institute of Social History

We shall

not consider here the event as it took place in the Amsterdam 'Beurs van

Berlage' building in september 1989 enlivened by exhibitions, concerts

and performances (2) but rather concentrate

on the genesis of the idea and the connections it has with the changes

that are taking place in the relations between Eastern and Western Europe.

An instant in point of the development in the thinking in the West is

the alternative press in Western Germany. It developed in the beginning

of the sixties from what was then called 'Minipresse' (Small presses)

and initially was predominantly literay. By the end of the sixties these

activities merged with 'pirate printing' no(t) (longer) available works

of authors like Adorno, Horkheimer and Reich, that became also the spiritual

food of the nascent student movement.

Criticisms of the developing 'manipulative mass culture' inspired direct

action such as the blockade of the buildings of the publishing firm Springer

in West Berlin in 1968 but also into the setting up of independent publishing

bodies, which started mainly with magazines but later on also brought

out pamphlets and books. Alongside the leftish student press there developed

also a press of the 'cultural underground' that showed its being different

not only by the contents of its publications but also by their deviating

form. The publishing landscape that came about in the course of the last

twenty-five years could be described as: small, independent, democratic,

left, radical, countercultural, alternative (3).

At the moment the number of 'alternative' periodicals coming out in the

Federal Republic amount to eight-nine hundred with printruns of between

a thousand and several tens of thousands. The highest is that of the West

Berlin 'Stadtmagazin Zitty' with a printrun of one hundred thousand which

means that in that city more copies are sold of this local magazine than

of 'Der Spiegel'. What makes a publication 'alternative' under such circumstances

? The regional alternative periodicals (Provinzblätter) are printed

in around a thousand copies.

To define a demarcation line between what is alternative and what is not

becomes particularly difficult in the case of the publishing houses. About

a hundred -hundred-fifty- publishers that may be described as alternative

bring out a total of a thousand to one thousand three hundred new titles

each year.

The print runs go from around three thousand to not less than thirty thousand

copies. 'Established left' publishers (Wagenbach, Rotbuch, Eichborn) with

yearly trade figures exceeding half a million of Deutschmarks justify

the designation 'alternative' only by the contents of some of their publications

(4).

"Stimulate the free and independent exchange of information in Europe

across the borders of the nation-states" was the aim of the Foundation

Europe Against the Current that we launched in 1987. Now in 1990, the

lack of understanding and the objections we had to cope with initially

when seeking funds for the event have become hardly imaginable.

After two year of seeking funds with only a few positive results we decided

yet to take the risk and to try to realize our 'maximum programme' with

a minimal budget.

Our manifesto said the Europe extended from the Urals to Iceland and from

the North Cape to Gibraltar but several 'European' bodies whom we approached

for funds still maintained then that Europe meant 'only the countries

of the European Community' and 'definitely not Eastern Europe'.

Still more difficult to believe for the national and international bodies

we approached for grants was our observation of the existence of a flourishing

alternative culture in Eastern Europe similar to that in the West. Did

not everybody know that over there was only grey grim oppression ?

In itself there was nothing new in our idea: "In order to define the real

dissidence it may be time for us in the West to put an end to our habit

of just lending some formal support to a few heroic personalities come

from the USSR or from Eastern Europe or still living there. It is time

to create a common basis for an understanding and active support of dissidence

the world over".

A quotation from David Cooper's 'Qui sont les dissidents ?' published

in 1977. Cooper compares "the subtle censorship and mystification in the

mass media and the educational process" of the West with the oppresive

methods used in the East. He attacks the intellectual laziness of those

who shout "Gulag! Gulag!" but are blind for the "megagulag of the West".

He agrees that "not-thinking" is a "prominent product of bureaucratic

socialism" but ist is equally "the price demanded by all the capytalist

systems".

A striking fact was that the oppositionist generation in the East with

which we got in touch by the end of the eighties was very determined in

their dismissal of the designation 'dissident'. That term had too much

to do with the cold war. The preferred and still prefer the word 'independent'.

In 1985, in the wake of the Helsinki accords, government representatives

from East and West met at an international conference 'The Cultural Forum'.

Almost all the European states as well as the United States and Cananda

spoke there about 'free cultural exchange'. The image of the culture to

be exchanged was traditional and unidimensional, however.

Alongside this official Forum an 'Alternative Forum' was held in Budapest,

organized by the Hungarian opposition and tolerated by the Kádár

regime walking on its last legs. In a short text for this Forum Susan

Sontag wrote: "Culture having the characteristics of a living being consists

of many parts. A culture that is only one thing -as all ideas about culture

monopolized by the State, any State- is a negation of culture (5).

This Alternative Forum was one of the sources of inspiration for 'Europe

Against the Current'. Other sources of inspiration were international

book fairs, in particular the Frankfurt Book Fair, the alternative 'Gegenbuchmesse'

held along side with it for about ten years, and the 'Black, Radical and

Third World Book Fair' in London. We dreamed of a combination of the positive

elements of these fairs without these disadvantages resulting in a new

inspiring whole: -of the Frankfurt Book Fair its truly internationalism,

its multiplicity of subjects and standpoints without its banalities and

sheer commercial aspect, -of the Gegenbuchmesse and the other alternative

fairs the low commercial profile, the informal atmosphere without the

tendencies in these circles to limit participation to people who share

the views of the organizers.

The East European participation had no precedent except for the representatives

of exile-publishers at the Frankfurt Book Fair, mostly Czechs, Slowaks,

Croats, mostly of extremely conservative kind. In october 1981, shortly

before Jaruzelski's putsch the official Frankfurt Book Fair housed the

first tiny stand of Polish samizdat publishers hidden far away from the

official Polish stand in the huge halls of the 'Messe'. The publications

on show there, graphically powerfull in spite of the extremely simple

means used, breathed a different atmosphere, evoked associations with

the 'cultural underground' in Western Europe and North America in the

sixties and seventies. (6).

In the

sixties and seventies Eastern Europe knew phenomena that were directly

connected with the cultural underground movement in the West but little

transpired of the direct contacts and information about them was scarce.

In the years 1965-1967 there were happenings in Prague in which the 'Aktúal'

group and one Milan Knizak played a role and about which some contacts

have existed with the international Fluxus as well as with Amsterdam Provo

movement.

Young Czechs who were excluded from rigorously reglemented cultural life

in their country because of their social origins, their insufficient education

or conflicts with the school system, started setting up their own bands,

created 'their own independent world outside the framework of the corrupt

world'.

The most

famous group were the 'Plastic People of the Universe' who performed in

the beginning of the seventies, mostly illegally, and were among the causes

of the foundation of Charta-77 because of the persecution of which they

were the object (7).

Worldwide protest movements, such as those in 1968, found some echo in

the Eastern countries, in particular in Yugoslavia, where in Belgrade,

in June 1968 students occupied the university and attacked the 'socialist

bureaucrats'. During the confrontations that took place in Prague in the

same year between inhabitants and Russian troops one Western journalist

was struck by the similarity in style: "People used hippie methods -they

put flowers on helmets and in rifle barrels. For the Russians that is

sheer frenzy..."(8).

Equally 'frenzy' methods, directed now against 'the country's own occupying

army' appear seven years later in Wroclaw and other Polish cities, when

Polish 'dwarfs' (similar to the Dutch 'kabouter' movement of the beginning

of the seventies) under the name of 'Pomaranczowa Alternatywa' ridiculize

Jaruzelski's military dictatorship with carnivalesque street happenings,

playfull graffitti and disarm it (9).

In a contribution written in 1989 for 'Europe Against the Current' young

art historian Mikhail Trofimenkov from Leningrad mentions the group 'Neo-eklektika',

poets who on the one hand feel close to the hippy movement, studied the

ideas of the 1968 movement, read Godard, Marcuse and Sontag, and on the

other hand declared themselves 'post-avantgardists' and applied methods

such as collage and 'ironical tautology'. The roots of this 'new counter

culture' Trofimenkov sees in poet and fiction writer Edward Limonov's

cult book "Edichka -that's me" written and published in exile at the end

of the seventies and situating its story in the fringe districts of New

York, apart from a few flash backs to Kharkov and Moscow (10).

In his quality of Russian exile Limonov is confronted with the less pleasant

aspects of freedom. The image this picture evokes of the incorrigible

rebel, of the man who rejects any system, who sees no difference between

the political structures of the USSR and the USA, together with the very

straightforward description of sexuality, homo as well as hetero, appealed

strongly to the young generation born during the second half of the fifties.

On the eve of Perestroika cultural free spaces are created through 'jumbo

exhibitions' in buildings awaiting demolition or renovation, where the

inner walls become temporary paintings. Blocks of houses are squatted

and turned into art galleries, workshops and alternative clubs. The prosecution

of samizdat publication lessens or stops altogether, better technical

equipment is acquired. Many 'underground' writers find their way to legal

publications such as the Latvian review 'Rodnik'. Trofimenkov concludes:

"It is possible nowadays in the Soviet Union to live undisturbed in the

new undergroudn rejecting both the conservative and the reformist (pro-Perestroika)

establishment (11).

The image of solitary resistance such as described as late as in 1977

by Russian writer Vladimir Bukovsky: "One is one's own writer, one's own

editor, one's own publisher, one's own censor, one's own distributor and

undergoes one's own punishment" has disappeared (12).

At the end of the eighties there is a change in prosecution policy in

some countries of the Eastern bloc, in particular in Hungary and de GDR.

Whereas initially the state tried to stop any expression of independent

thinking by repression, to have too many political prisoners, too many

potential matyrs became a nuissance for these states. Human rights organizations

in the West and the desirability of economic contacts with countries outside

the Eastern bloc make their pressure felt. The prosecution policy develops

gradually towards limiting the volume of independent literature. Prisons

sentences become rare but equipement and publications are seized and fines

imposed.

In the GDR fines range from five hundred to five thousand marks. They

imposed not only for illegal publishing but for any form of opposition

to the power wielders such as long hair or a punk hair. Fines were often

collected by distraint on wages, leaving people with not more than a bare

subsistance income (13).

In Hungary the homes of persons known to be printers or distributors of

samizdat were often searched. In case a 'roneo' machine or other multiplying

equipment was found it was seized, so that samizdat publishers fell back

to the more primitive device of the stencil frame, simple to hide, easy

and cheap to replace. A samizdat publisher had during eight years through

various contacts his printwork done in state enterprises against black

payment. He was caught only once during all that time. This happened when

he came to collect an order hot from the press. He was fined five thousand

forint and managed to continue his activities (14).

In Czechoslovakia repression was not as absolute as is often thought either.

At the same time as when the state security services take action against

the in their view excessive cultural activities of the (legal) Jazz Section

Prague leading to a prison sentence for one of its members, simular initiatives

are tolerated, or better not actively prosecuted. One example is the magazine

'Revolver Revu', a radical cultural and literary periodical of which the

authorities knwe exactly who made it and where. In the course of five

years thirteen fat issues (of three hundred to four hundred pages) were

allowed to appear. During this time the roneoed and photocopied printrun

increased from fifty to five hundred copies with a readership that can

be estimated at ten times this number. For Czechoslovakia this were exceptionally

high printruns. As a rule Czechoslovak samizdat was multiplied in minimal

quantities with typewriters carbon paper and thin paper allowing a maximum

of about twelve readable copies. The publishers of a similar review 'Vokno'

were prosecuted, those of 'Revolver Revu' were not. But on a bad day the

house were the review used to be made was destroyed in afire of which

the causes have never been established. The editors of Revolver Revu hold

that the state security services have been behind it (15).

In Poland the underground press had become so big that they became competitors

of the state publishing houses both in content and in size. Jaruzelski's

coup in 1981 involving, under martirial law then in force, the cancellation

of more than two hundred contracts with authors working legally until

then and the boycott of the regime by intellectuals initiated at that

time, only reinforced this development. In 1985 there was talk of between

five hundred and one thousand independent periodicals in Poland printed

in from one hundred to several ten thousands of copies (16)

All this

in spite of the initial risks of seizure and prison sentences of several

years. The size of this illegal production ment also that the pureness

and the idealism that seemed to have to accompany samizdat publishing,

disappeared. Necessary materials had to be bought at the black market

which resulted in connections with more commercial interests.

In Yugoslavia the situation was different in the eighties. The existing

structures, in particular the cultural youth organizations, had been offering

since a number of years, be it limited, possibilities to express dissenting

opinions. Student cultural centres at Lublyana, Zagreb and Belgrade have

been turned into centres for radical avantgardes that bear comparison

with progressive cultural centres in Western Europe.

In principle

publications are sighted by the censor after printing. This means that

in several cases publications displeasing the state can yet be published

and be sold out before the public prosecutor has had the opportunity to

forbid them. The ever stronger national dissensions within the fedaration

have also increased the elbowroom for opposition groups. Endeavours to

repress intellectuals taking an independant stand as in the case of the

trial against what were called the 'Belgrade Six' in 1984 failed also

for this reason.

A case in point is the evolution of the Slovenian monthly 'Mladina' set

up in 1943 as the youth magazine of the communist party. In 1984 the moribund

publication was turned into a teenagerly 'fanzine' of which the circulation

rose initially to a modest seven thousand copies. But the young hip journalist

did not stop at pop events and the review became a political oppositional

paper that soon gained unbelievable popularity. The relevation of corruption

scandals in Slovenia drove the circulation up to thirty thousand. The

arrest of editors elicited strong protest, pushed the circulation to seventy

thousand copies and confered the magazine country wide importance in 1987-1988

in spite of differences between the Slovanian and other Serbokroatian

languages. "We are the official press, they the alternative one", claimed

'Mladina' editors with proud boldness at a congress about alternative

youth culture in Southern Europe in Bologna in December 1988.

The 'Europe Against the Current' event in September 1989 attracted three

hundred fifty participating groups from twenty-one countries. The multiformity,

the multiplicity of opinions sought by the organizers was achieved but

not all the participants and visitors were happy with it. The culturally

oriented found the event too political, the politicals blamed its far

too cultural character.

The participants

from Eastern Europe, mostly for the first time in the West, were often

surprised to see the Western European radical left groups present. Their

passionate stand was exactly what they sought to free themselves of or

what they tried at least to flee.

The Czech philosopher Václav Benda coined in 1978 the expression

'paralelnípolis' for structures keeping outside the state sphere

of influence that follow their own standards and have their own means

of communication (17). Under the existing

circumstances it was maybe the only option at the time. But in other social

conditions such a situation can result in suffocating ghettoing. This

goes for both Western and Eastern Europe.

To withdraw from society can be a necessary condition to discover or to

experience other possibilities and values. Lasting separation may jeopardize

such gains, however.

The price paid for social experiments in Eastern Europe was so high that

utopian endeavours are now viewed there with great fear. The Russian samizdat

author Venedikt Jerofejev says that he "would liked to live on this earth

forever provided I had first seen a small corner that is not always the

scene of big deeds" (18).

Are there

other options than either to participate in the existing order or to withdraw

in one's own subculture ?

The idea behind 'Europe Against the Current' was and is to offer

recurrent opportunities to show alternative possibilities and views, to

confront 'mainstream' Europe with all that may describe itself as 'alternative',

'independent' or 'radical', to be an inspiring force that prevents European

unity to become European uniformity.

Tjebbe van Tijen

[draft translation of an article in the dutch magazine "De Gids", may

1990 by Tjebbe van Tijen, translator Bas Moreel]

1.

Number of groups entered in the database (situation september 1989):

Belgium 357, Denmark 29, Great Brittan 644, France 335, Hungary 39, Italy

358, Yugoslavia 58, The Netherlands 410, Norway 17, Austria 83, Eastern

Germany 11, Poland 51, Portugal 28, Soviet Union 297 (taken mostly from

a list of 600 groups published in 1989 by oppositional trade union SMOT

in Moscow), Spain 206, Czechoslovakia 20, Western Germany 602, Sweden

36, Switzerland 173, Iceland 4.

A selection of 988, of which 60 with a short description in English has

been published by the Foundation EAC in cooperation with the ID Archiv

in the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

2. A report in English and German was published as a special supplement tot the West German Magazine 'Contraste', january 1990. Available from Foundation Europe Against the Current, Jodenbreestraat 24, 10110 NK Amsterdam

3. A detailed description can be found in Helmut Volpers "Alternative Kleinverlage in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland", Göttingen 1986.

4. Data supplied by ID-Archiv im IISG, Amsterdam/Frankfurt.

5. Quotation from "A magyar szamizdat 5 éve/Bibliography of Hungarian printed political samizdat" published at Budapest in November 1985 by Gábor Demsky and László Rajk on the occasion of the Cultural Forum.

6. Among the publications on display were those Wydaw ABC, Kraków.

7. Data taken from a text by I. Jirous, leader of popgroup Plastic People, initially circulated in samizdat in 1975 and subsequently published in the magazine 'Index on Censorship', London no.1 1983.

8. In "The imagination of the New Left: a global analysis of 1968" by George Katsiaficas, Boston 1987.

9. A refreshing documentary film 'Majór' was made on this subject in 1989 by the Polish filmmaker Maria Zmarz-Koczanowicz. It was shown in the 'Fresh from Warsaw' film festival in Cinema Desmet, Amsterdam summer 1990.

10. New York 1979.

11. See note 2.

12. From "I vozvrascaetsja veter"..

13. Taken form an interview made by the author in April 1990 with a member of the group 'Wolfpelz' in Dresden.

14. Taken from coversations an interview made by the author in January 1989 and May 1990 with Aramlat publisher in Budapest.

15. Taken from an interview in May 1990 by the author with an editor of Revolver Revu.

16.

Taken form Dorota Lesczynska and Reinold Vetter, "Die unabhängige

kulturelle Bewegung in Polen", published in Osteuropa-Info No.64, Berlin

(West) 1985.

17. Manuscript multiplied by typewriter, quoted in

"Auf der Suche nach Autonomie: Kultur und Gesellschaft in Osteuropa",

D. Beyrau and W. Eichwede (editor), Bremen 1987.

18. "Moskva = Peutushki" (1969), "Moscow Circles" in the English translation, London 1981.