Visuals & text delivered at the Phd defence by Stephanie Gautier-Benzaquen December 22, 2016 at Erasmus University Rotterdam.

[1] A couple of years ago, as I was doing research for my dissertation at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, I came across the archives of artist Tom Küsters, born in 1943 deceased in 2008.

Throughout the Seventies Küsters had been a member of a group of students and activists from Nijmegen part of the anti-Vienam War movement of those days.

After that war was finished Küsters also supported the upcoming Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, that was closely linked with the People's Republic of China.

These students organized demonstrations, meetings, and exhibitions, published books and magazines about it.

After the death of Tom Küsters, his papers and archival material were donated to the Institute in Amsterdam.

Some of the leaflets, posters, stickers, and postcards in the collection have the name of Küsters printed on them, signing them as a designer and artist. Designs were made on the basis the information and propaganda imagery supplied by the Khmer Rouge regime.

I dug into Küsters’s archives enthusiastically, hoping to gather more information about how he got these images and who was his contact person in the Khmer Rouge movement.

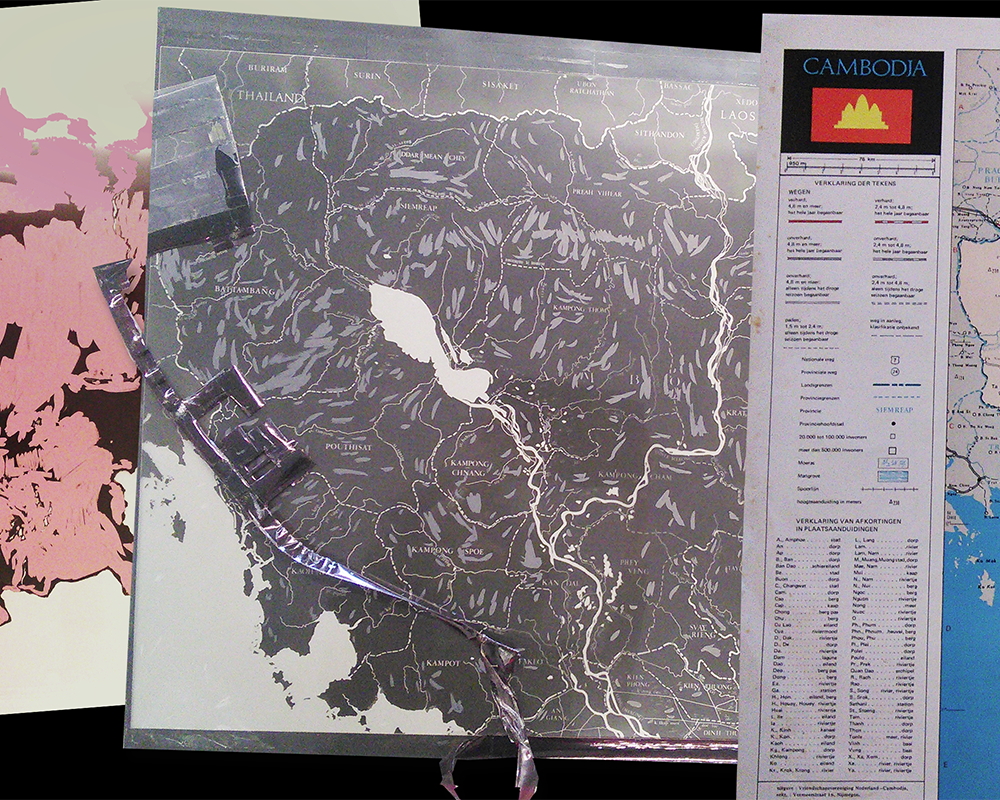

[2]

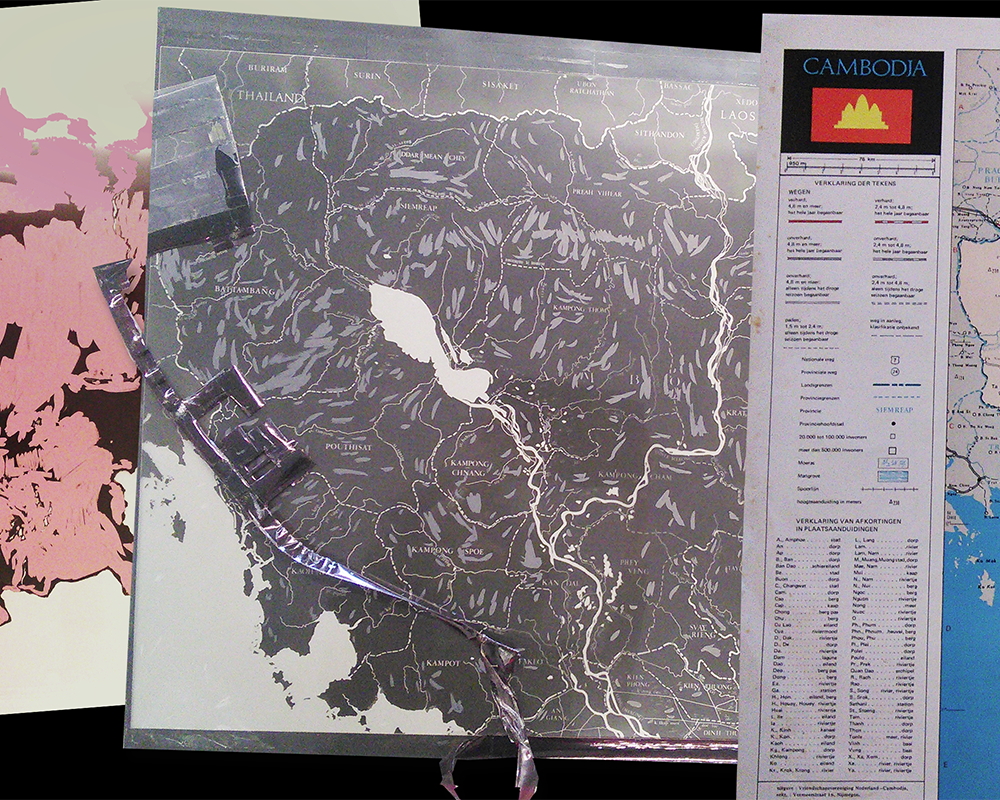

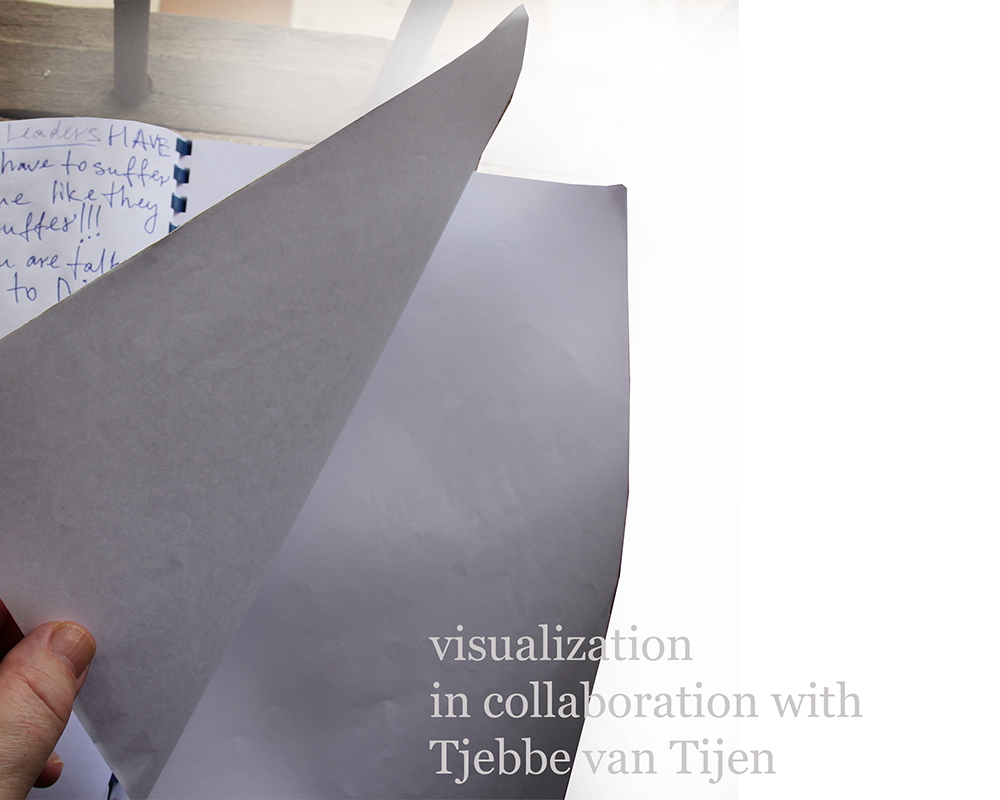

Yet, I discovered in the boxes something fascinating: the color sheets, negatives, cutouts, and prints Küsters had used to create a Dutch language map of 'Democratic Kampuchea', as the Khmer Rouge regime had officially renamed Cambodia in 1976.

Unfortunately, little was to be found. Either Küsters had got rid of the documents himself, or his archives had been purged before donation.

Needless to say, such a friendship with a genocidal regime was an embarrassing memory.

Thanks to this material, it is possible to reconstruct the process by which a blank, uncharted space progressively becomes visible, as rivers, mountains, cities, and roads are added. The final layer was the zones the Khmer Rouge had devised in the place of the traditional administrative divisions of Cambodia.

I see a symbolic dimension in the mapping work of Küsters, a parallel between the process of creation of the map and the geographic act of the Khmer Rouge themselves, looking at Cambodia as terra nullius—a nobody’s land—upon which to imprint their political imagination.

[3] This map making example provided me with a metaphor for my own research. When I began my study of the visualization of Khmer Rouge atrocities I too had the feeling that I was facing a blank slate.

Then, contours appeared and I began adding layer upon layer.

It is often assumed that the Cambodian Genocide — as the crimes of the Pol Pot regime are frequently referred to — Is rendered invisible.

First due to the dominant idea in post-Holocaust culture that such an event, exceeding any form of language, cannot be represented

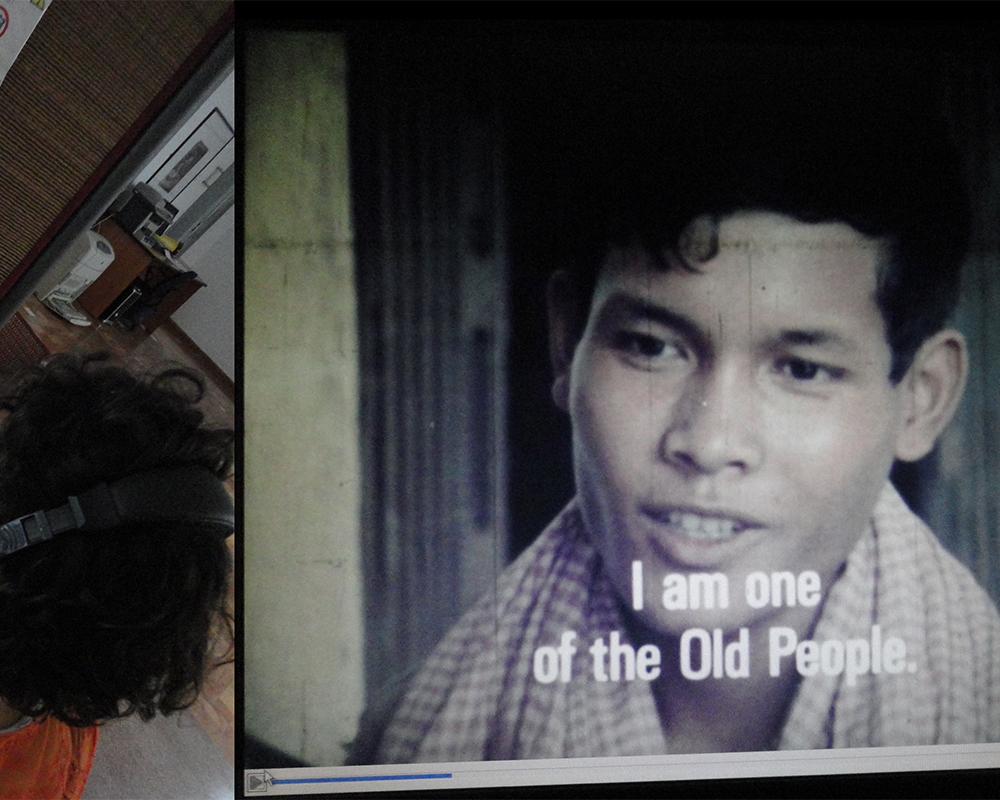

Second, as a crime perpetrated by a regime that was itself invisible, hiding behind the faceless and shadowy organization named 'Angkar' (the word means organization in Khmer).

People in Cambodia hardly knew who the leaders were, or what they wanted to achieve. It is as if 'Year Zero' —the term used to describe the Khmer Rouge attempt to reset Cambodia through extreme violence—had left no trace.

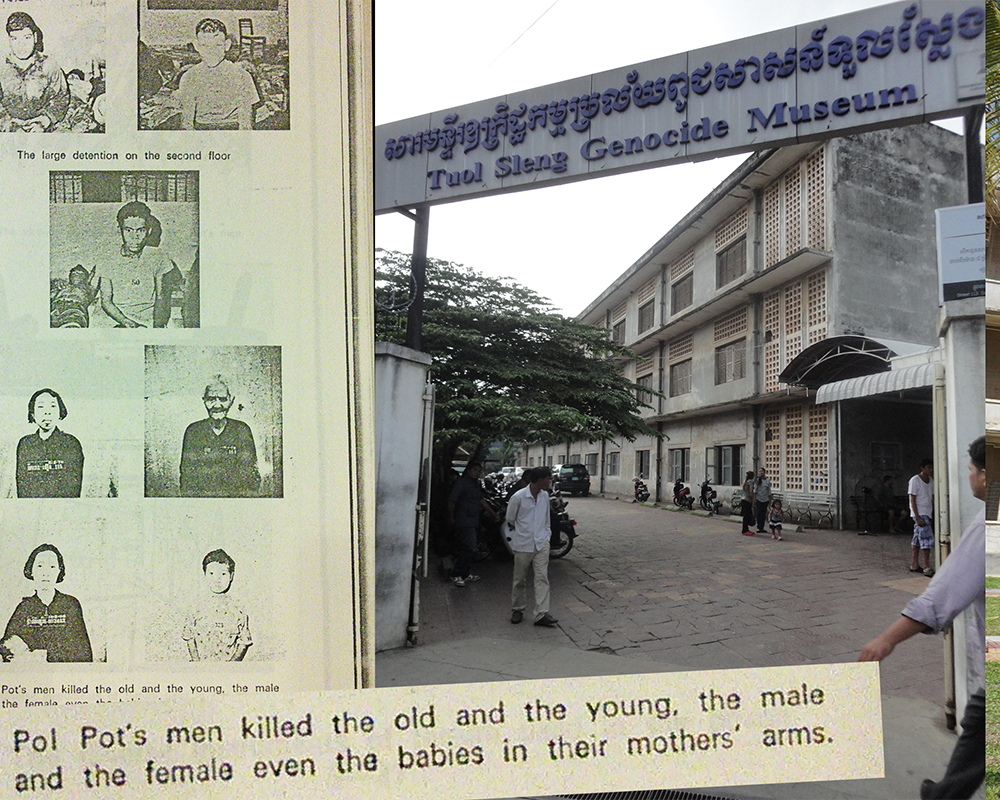

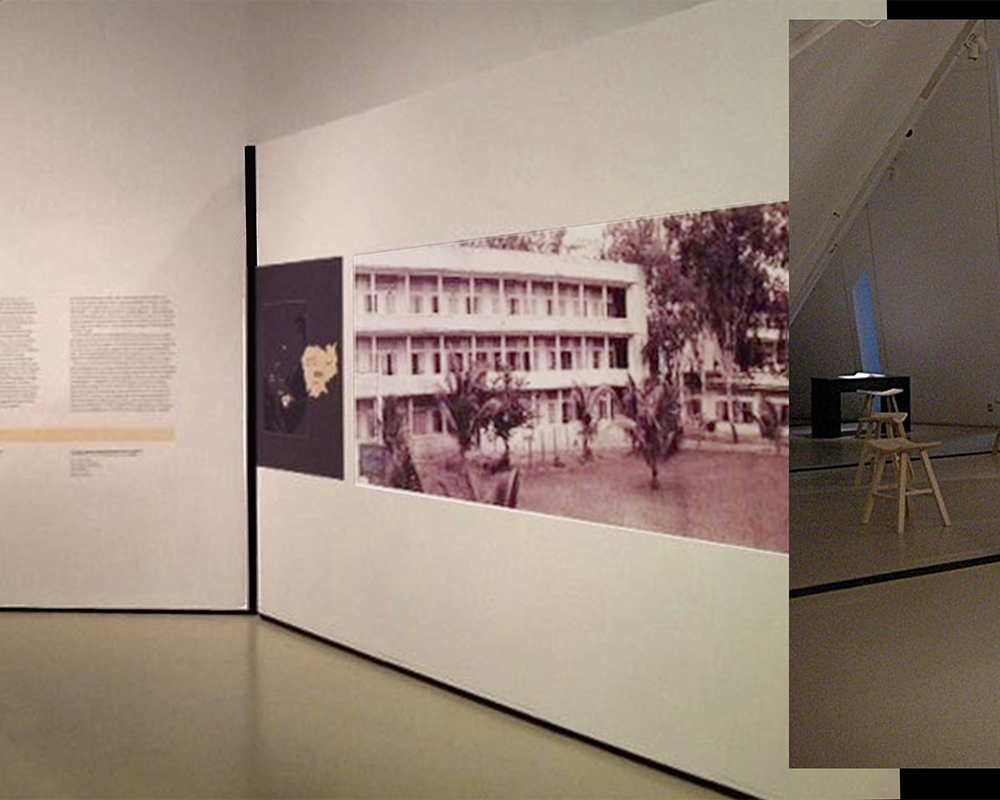

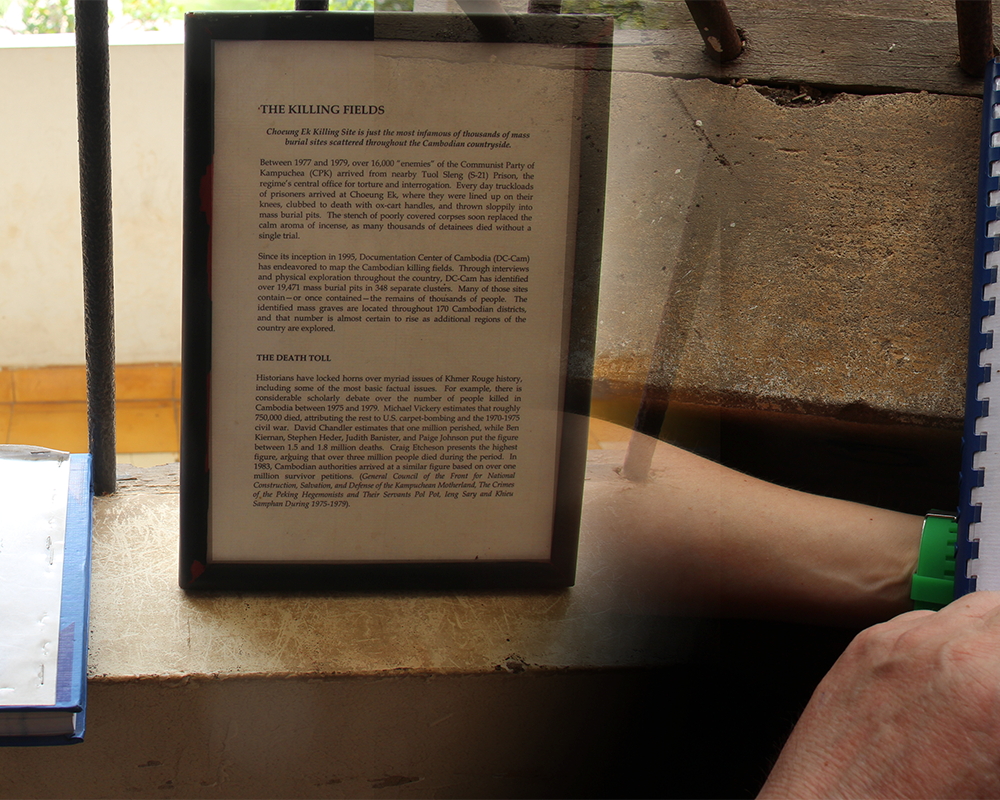

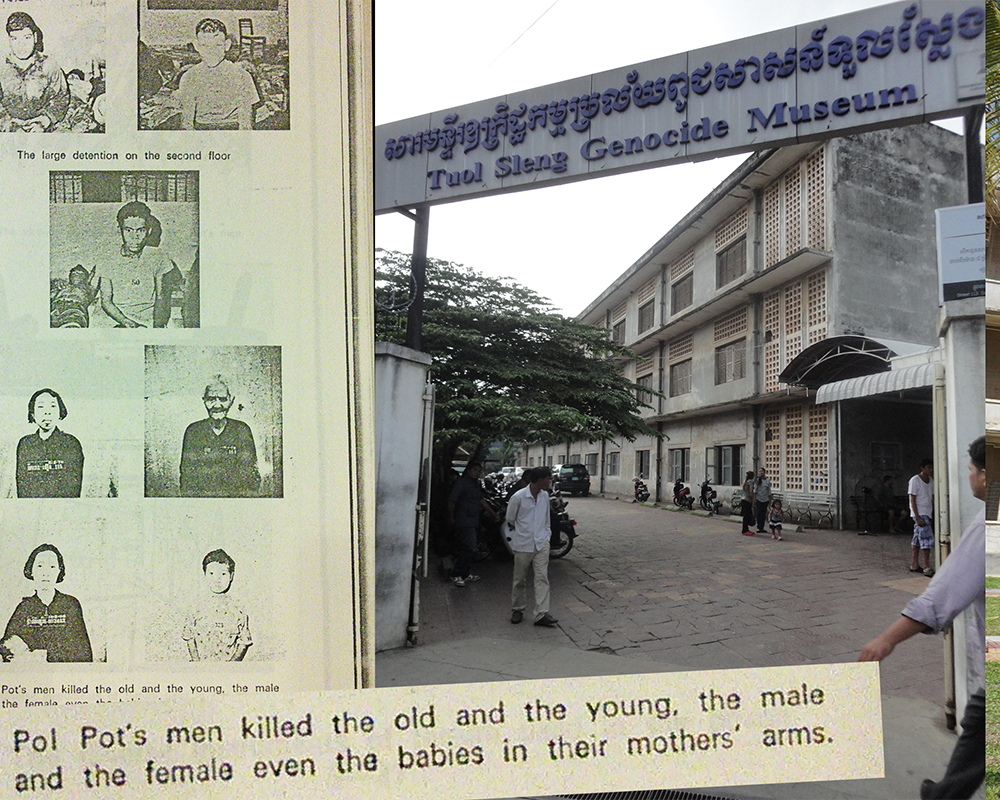

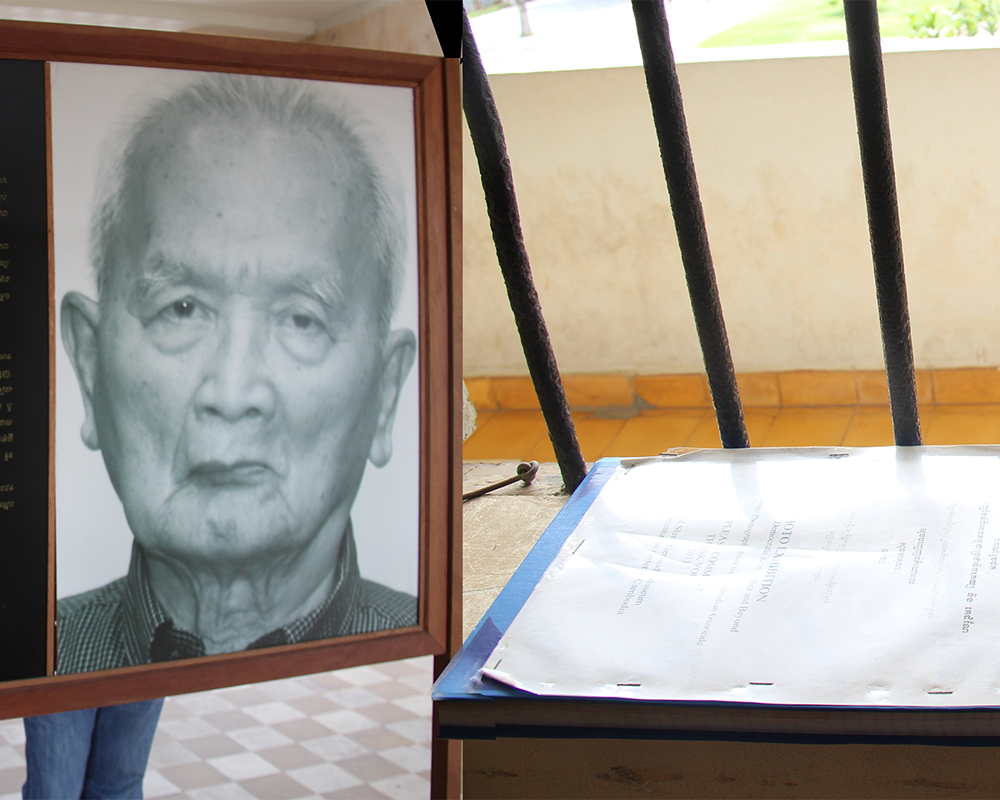

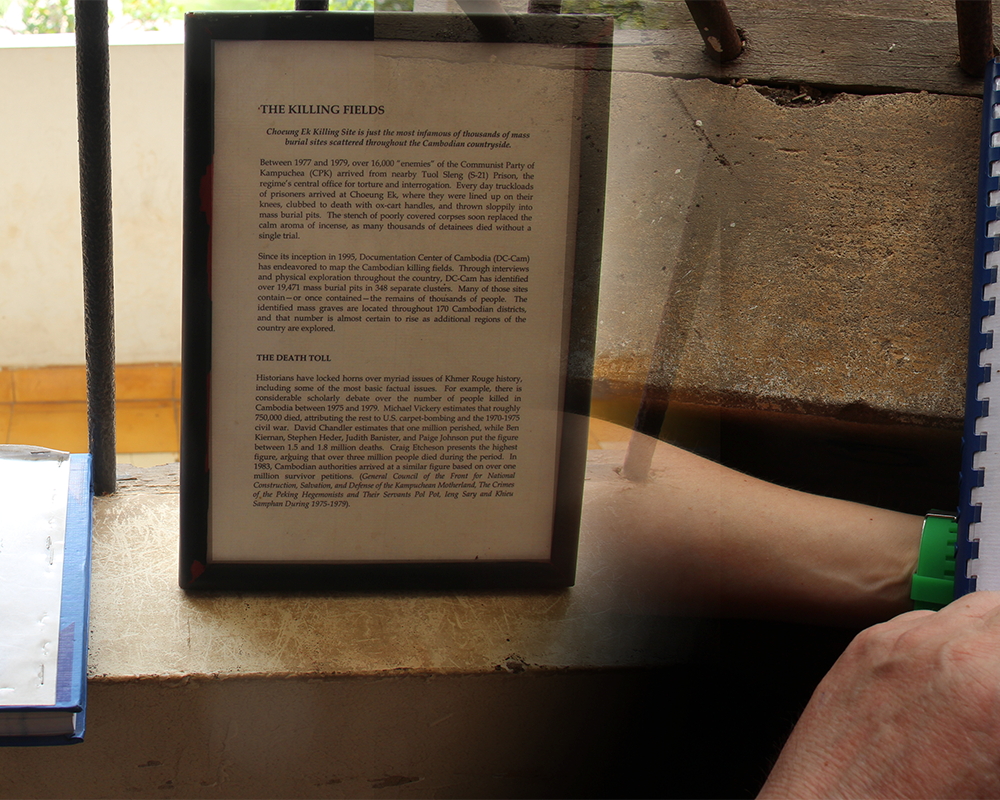

[4] Only a limited set of records might be defined as direct visual evidence of Khmer Rouge terror.

These are the photos of S-21 prisoners.

S-21, or Tuol Sleng, was a former high school in Phnom Penh turned by the Khmer Rouge into a torture and execution center.

The prisoners—thousands of men, women, and children—were photographed upon arrival and the picture attached to their confession file as a means of identification.

Later on, when the site was converted into a memorial museum, this bureaucratic recording of extermination was displayed on the walls as a powerful reminder of the cruelty of the Pol Pot regime.

Over the years the black-and-white mug shots became iconic images of Democratic Kampuchea terror, used in books, press articles, television news, documentary and fiction movies, social media, public exhibitions, and works of art.

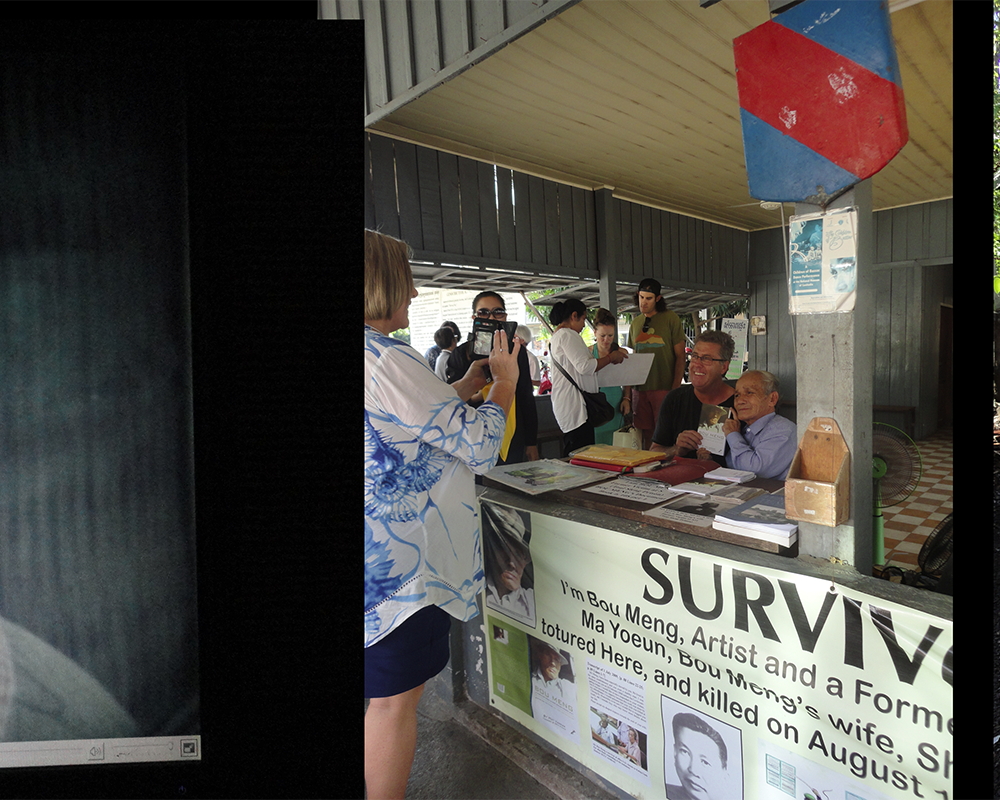

For many people, in Cambodia and abroad, these photos are an emotional connection to the past.

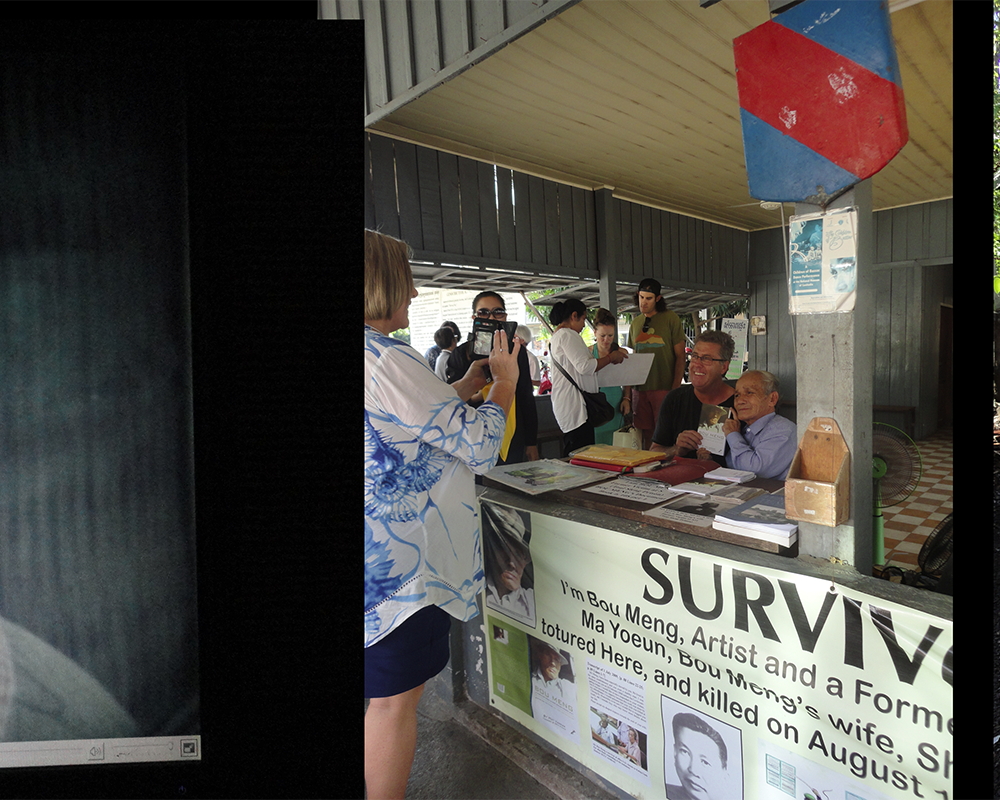

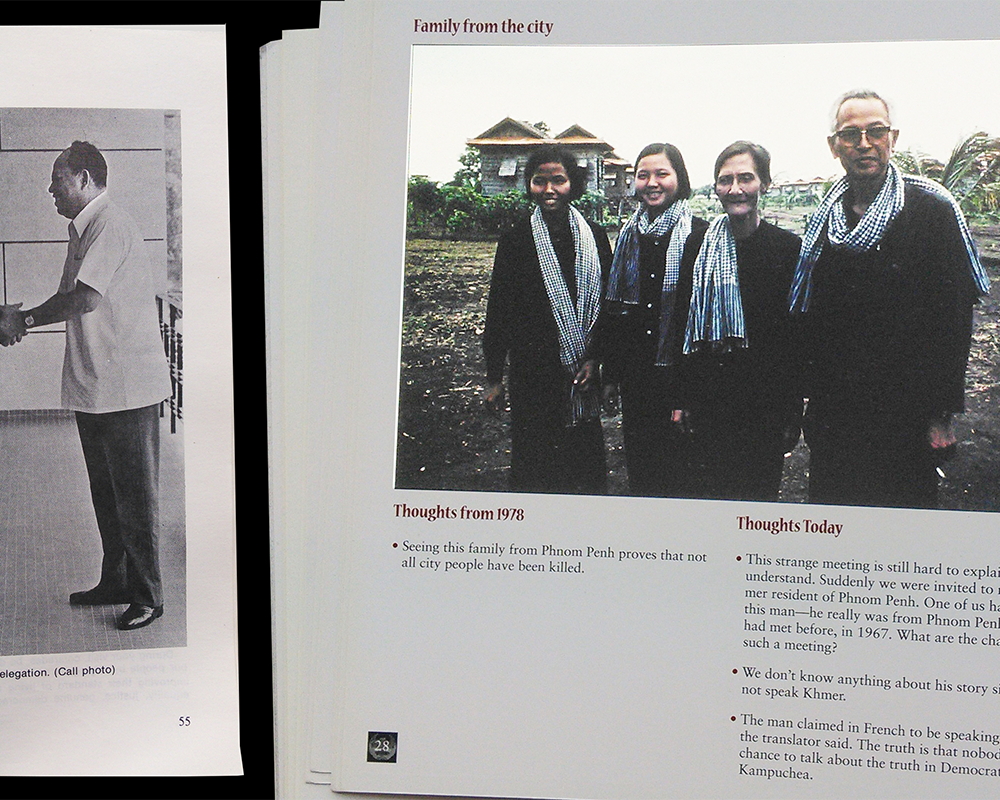

[5] But is that all? When one speaks of images of Khmer Rouge atrocities, should one consider only images that have a proof value in court? What to do then with other kinds of images such as:

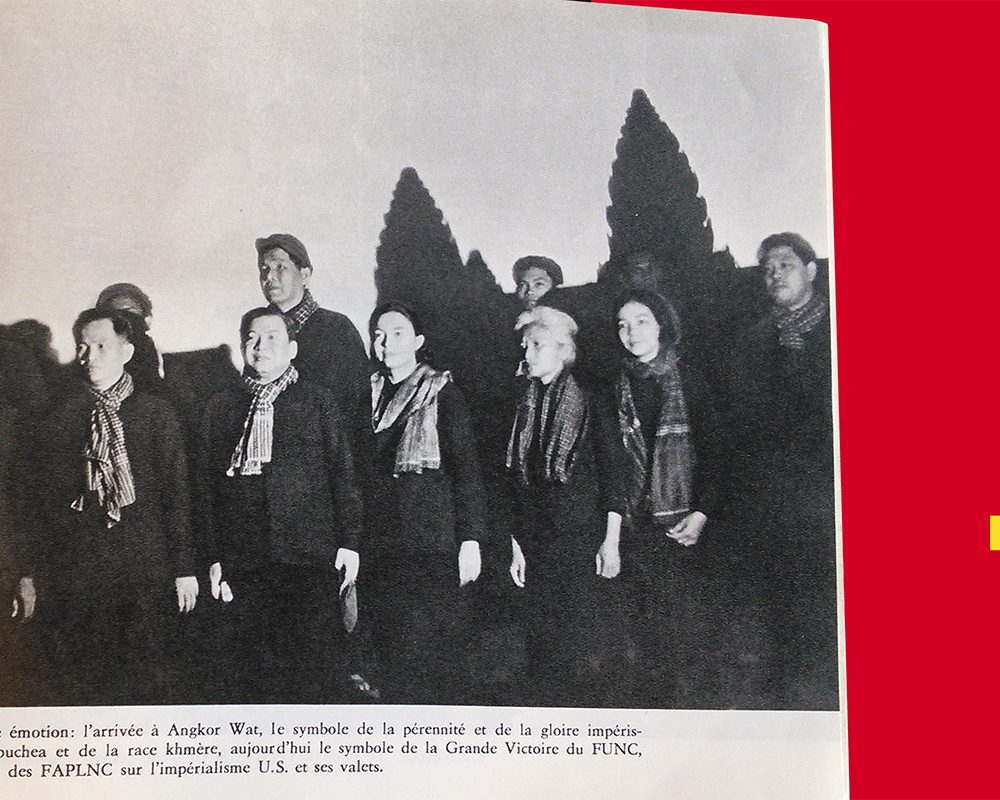

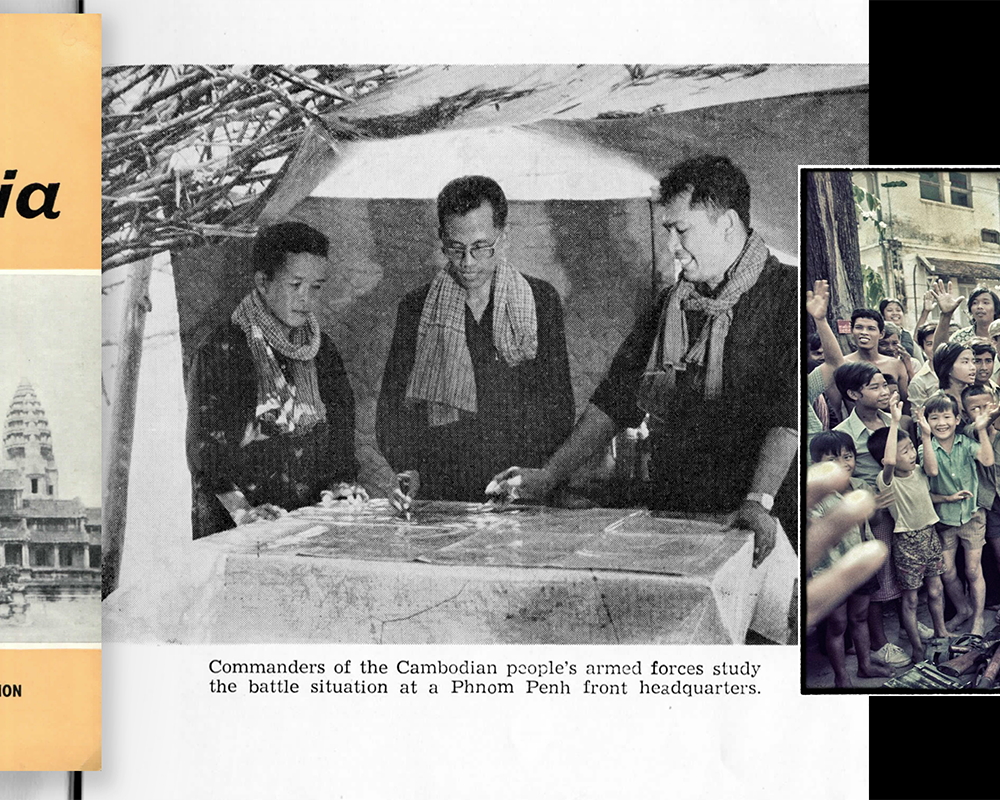

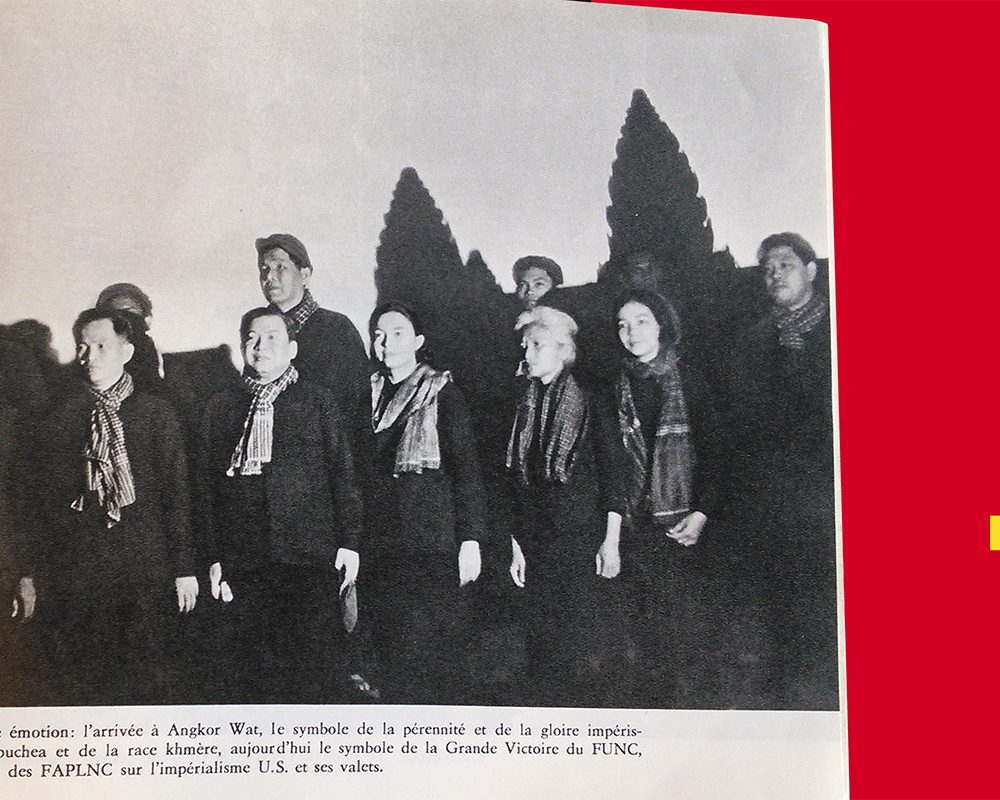

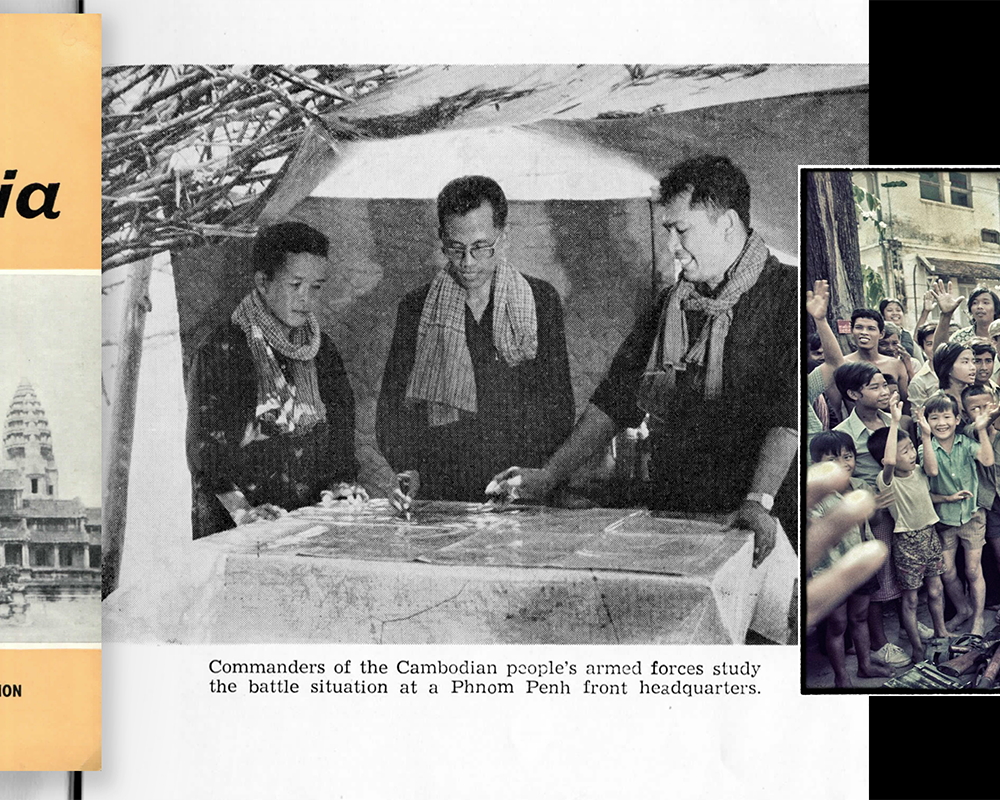

- the Khmer Rouge propaganda photos showing the great achievements of the Angkar;

- the Vietnamese records documenting the reconstruction of Cambodia in post-Democratic Kampuchea years;

- the illustrated reports of foreign fellow travelers, journalists, and humanitarian workers;

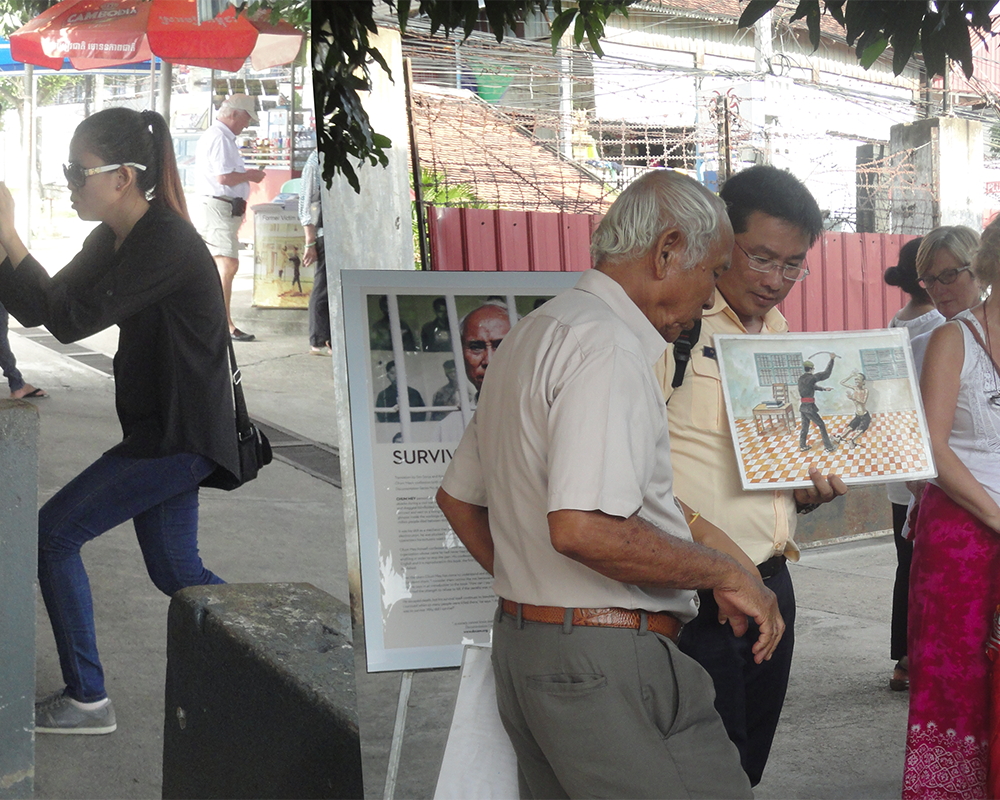

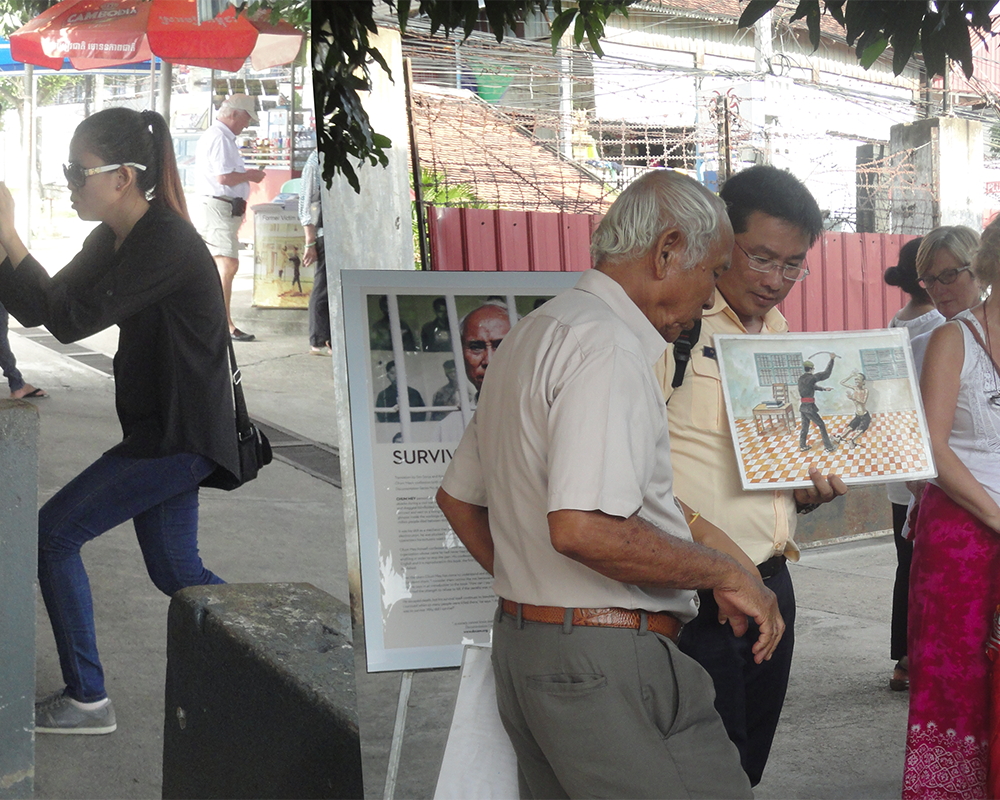

- the works of survivors and second-generation Cambodians;

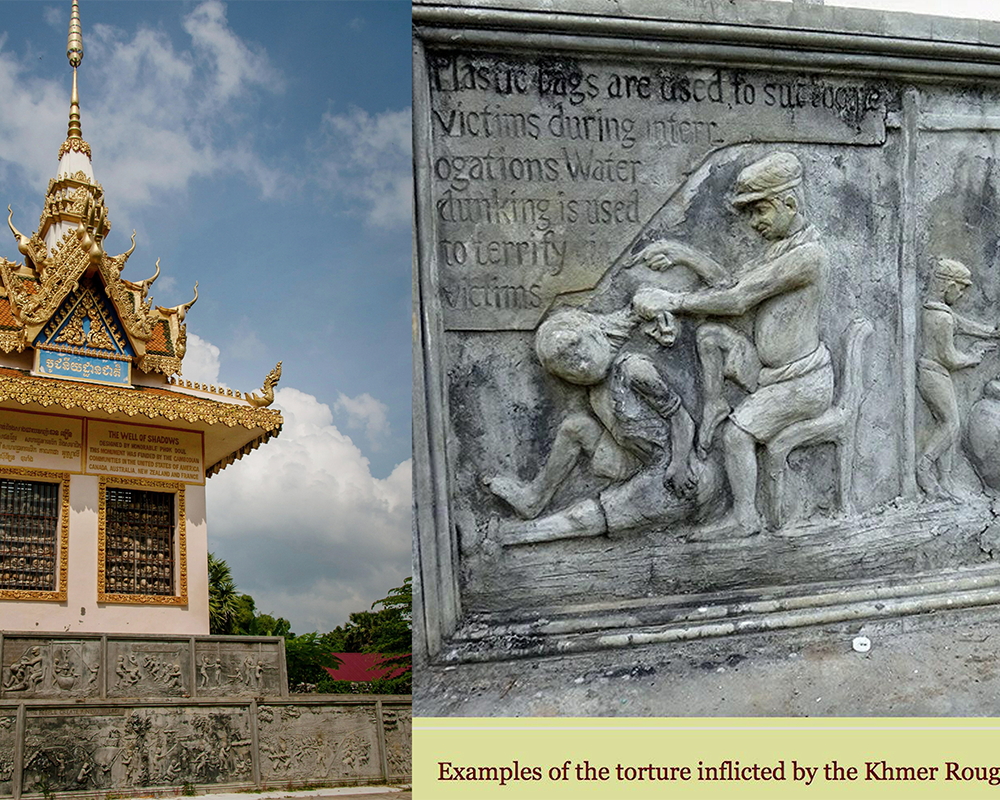

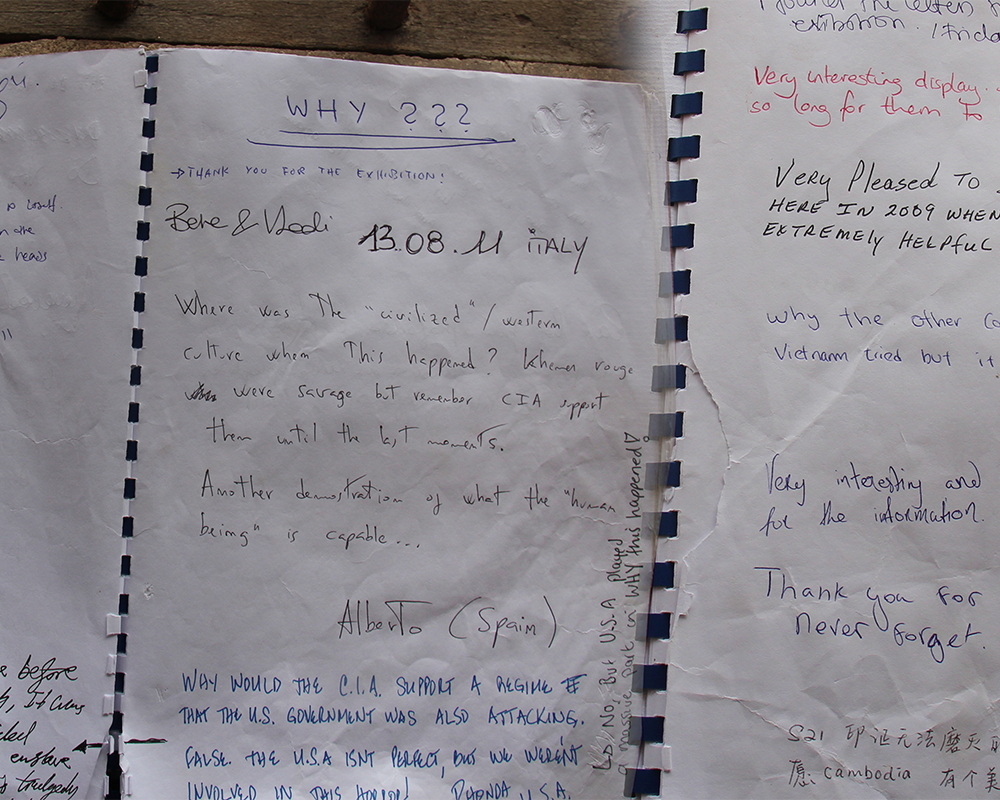

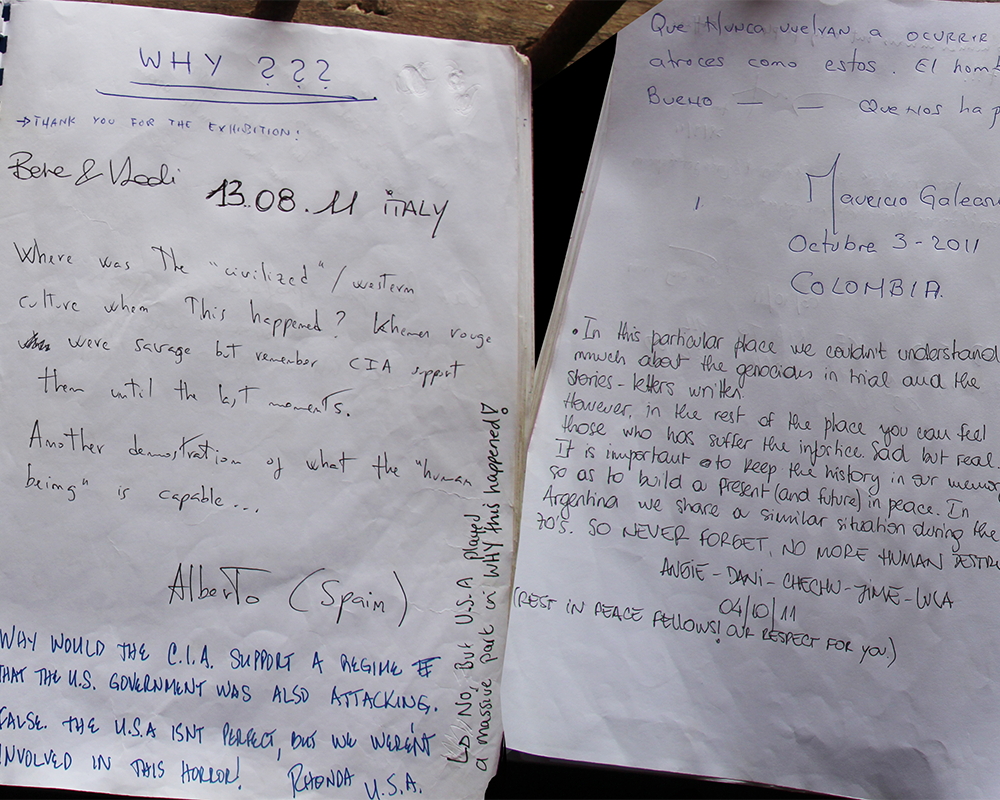

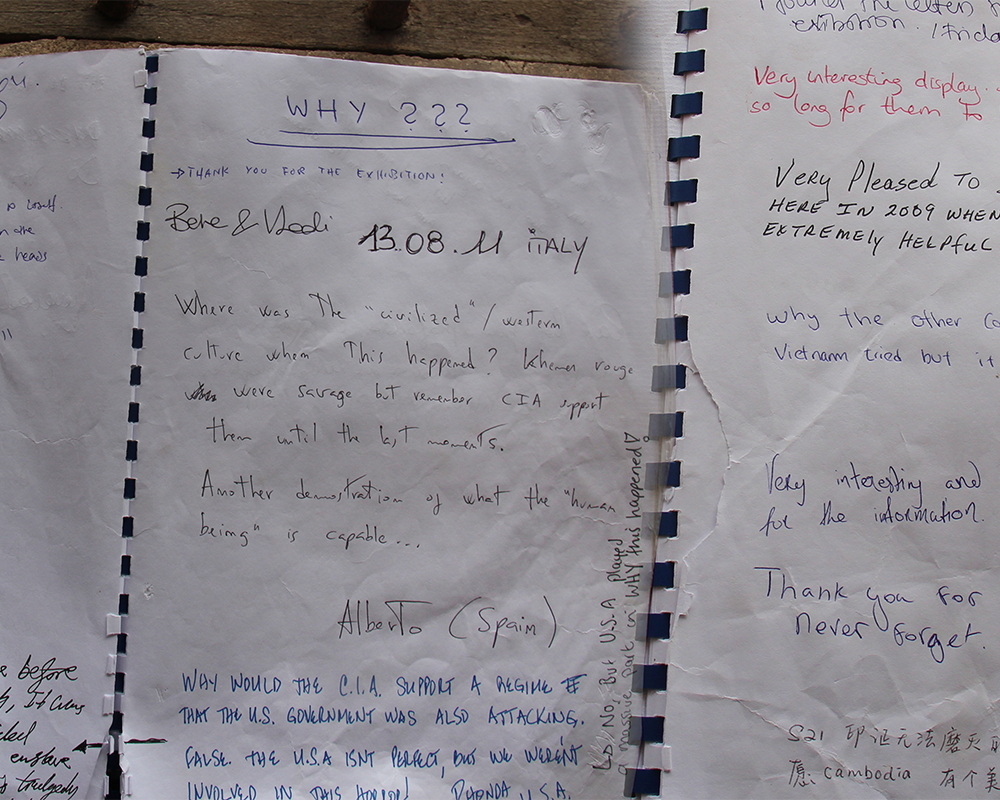

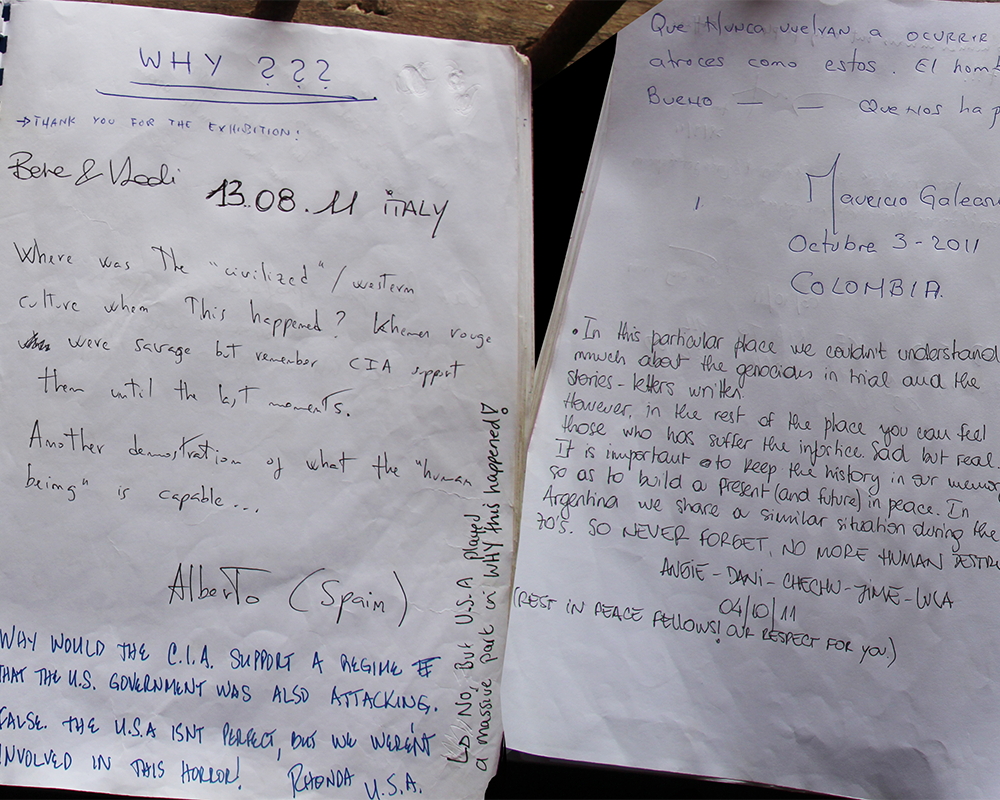

- the visual material produced in the context of transitional justice and dark tourism.

Are these not images of the Khmer Rouge regime as well, depicting another moment, another aspect of the Cambodian Genocide?

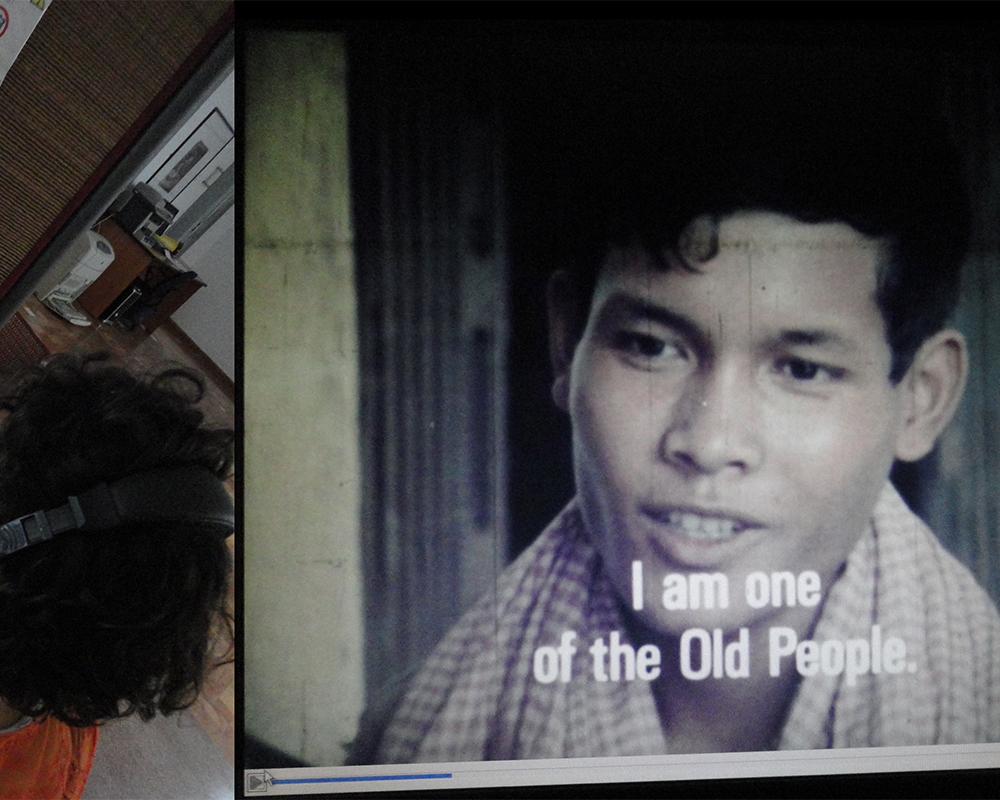

[6] In 2013 Cambodian-born film director Rithy Panh released the movie The Missing Image, in which he brings together his personal recollection of the Democratic Kampuchea years (he was deported to the countryside with his family and lost many relatives) with Cambodia’s collective history through archive footage, dioramas, and video.

As his previous works, the film reflects on the role of images in remembering the Khmer Rouge regime.

I take my cue from Rithy Panh, and define my research as an attempt to gather, assemble, and connect all kinds of images selected across a period of forty years in order to create a more complete view of the event and the way it is remembered.

[7] The picture emerging out of this work process reveals the complexity and changing nature of the visualization of Khmer Rouge atrocities from 1975 to the present-day.

Cambodia itself transitioned from socialist republic to multiparty kingdom, and from state-controlled to free market economy.

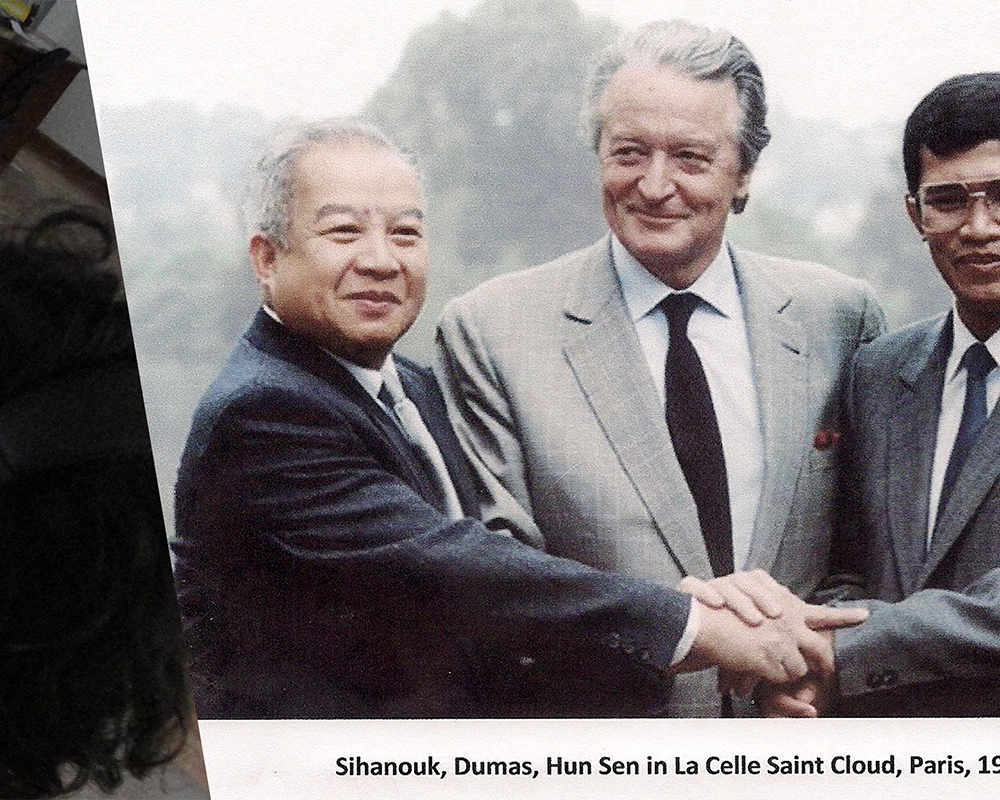

It shows that the people, groups, communities, organizations, and governments involved in the writing of the Democratic Kampuchea past come from all over the world, all the more so since Cambodia opened to mass tourism in the last two decades

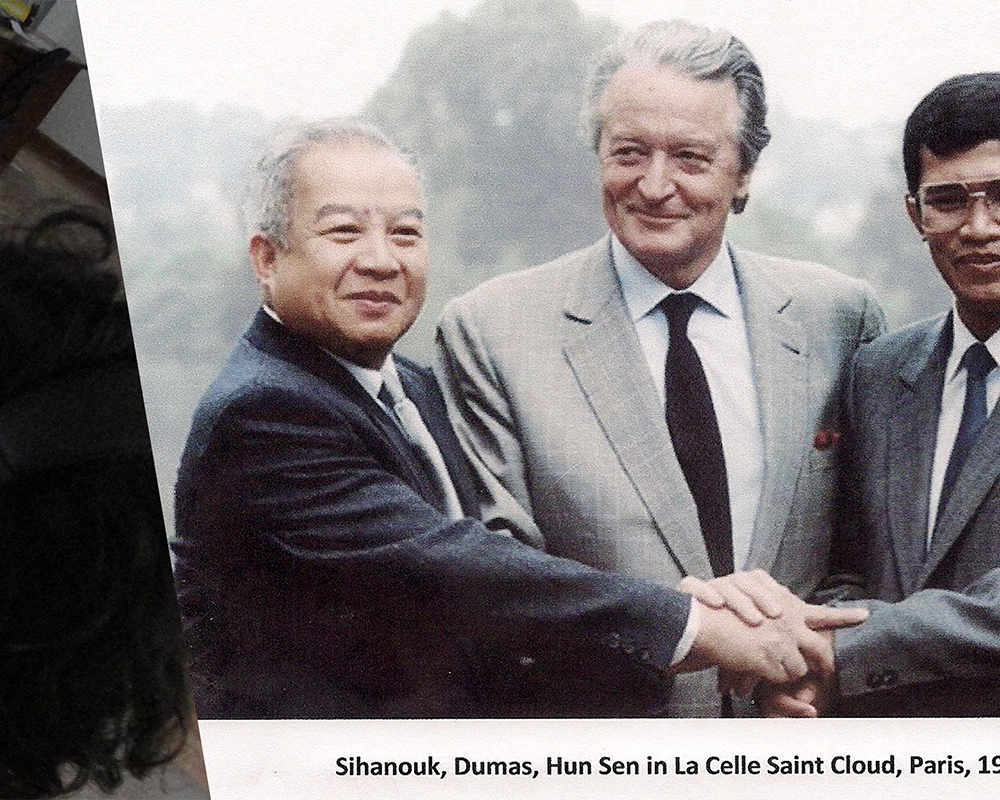

The story of the Khmer Rouge, thus, deploys across borders and eras, from the Cold War to the post-Cold War period, through different forms of colonization, woven into a web of transnational relations, ideologies, and narratives.

[8] It is through the concept of "Khmer Rouge visual culture" that I approached the task of clarifying this web and how it expresses through visual forms.

This notion—I am aware of the fact—demands that it be further elaborated and possibly renamed.

Some might have difficulty putting together, under the same umbrella, the propaganda of the murderous Pol Pot regime and the long-term recovery of cultural memory initiated by Rithy Panh and followed by others.

Still, the idea of “Khmer Rouge visual culture” provides the researcher with a unifying framework for looking at a wide and diverse range of artifacts and tracing continuity, shifts, and fusions between them.

My goal is transcending different categories of images, such as: - archive images and the afterimage they produce; - artistic and documentary images; - popular and experimental and artistic images.

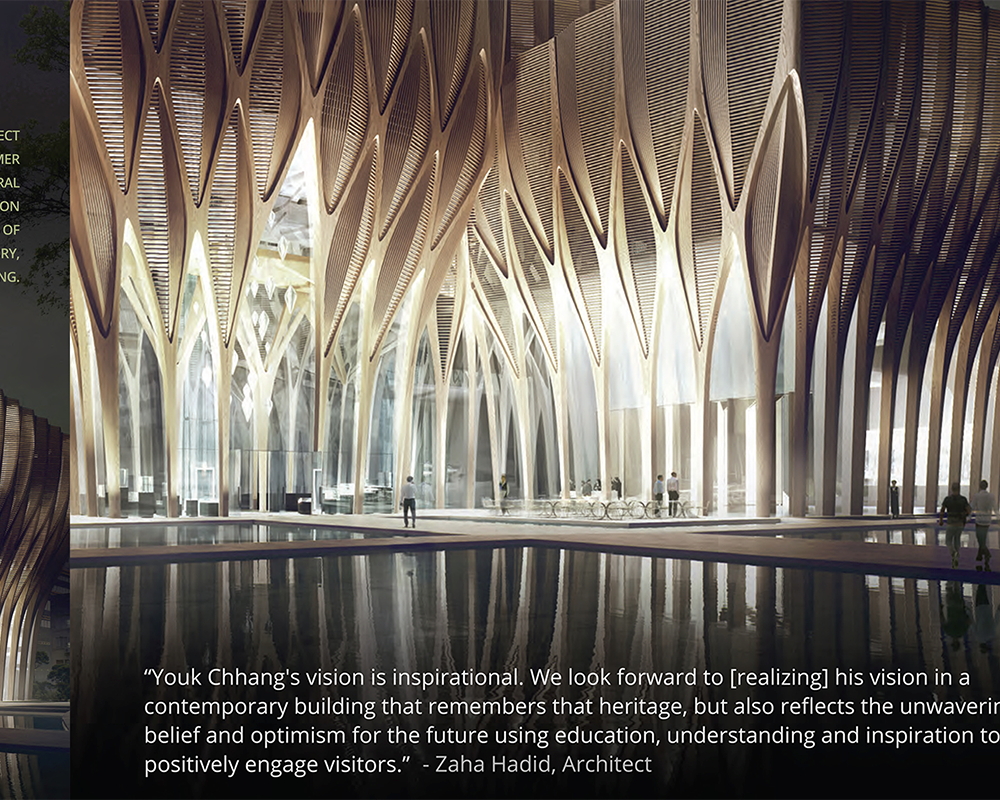

This will help open up a broader understanding of images of Khmer Rouge crimes, not only as bearing witness to destruction and extermination, but also as being active agents in processes of coming to terms and reconstruction.

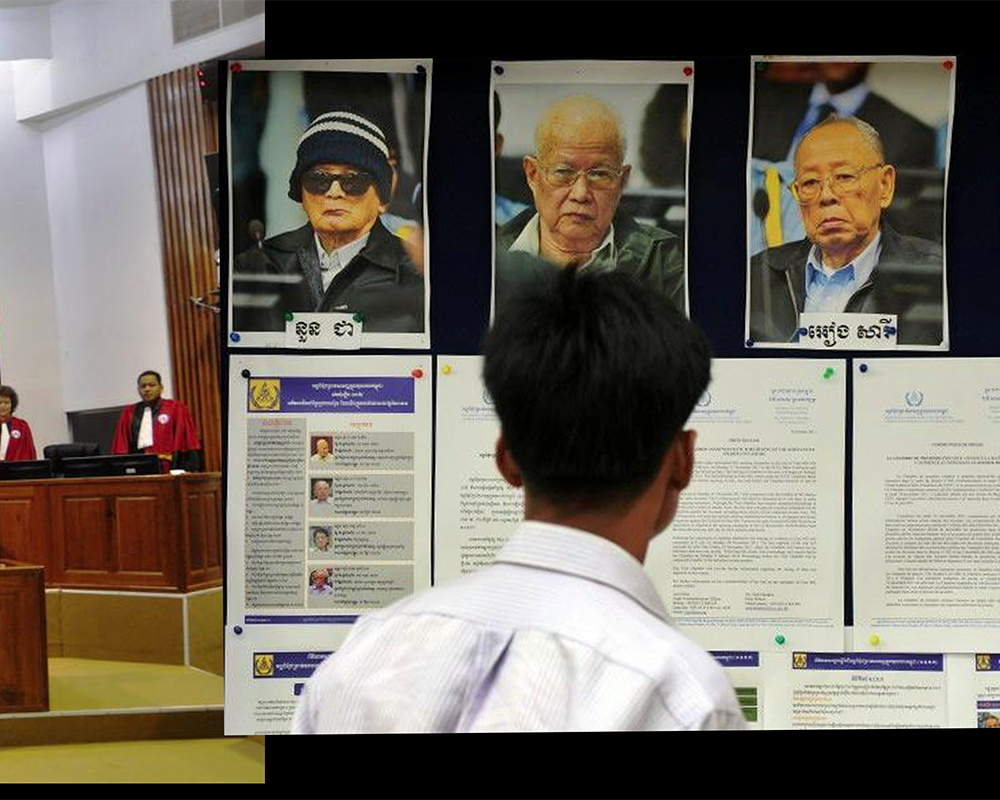

[9] For a long time Khmer Rouge-related studies have been focused on history and political science. In the past twenty years, anthropology has come to play an increasingly important role, pioneering new perspectives on the Khmer Rouge regime and Democratic Kampuchea society.

Visual culture, though, is a newcomer in this specific academic realm, and as such offers no readymade theoretical construct. Those exploring this new territory need thus to create their own tools of investigation and give them the reality test of empirical research.

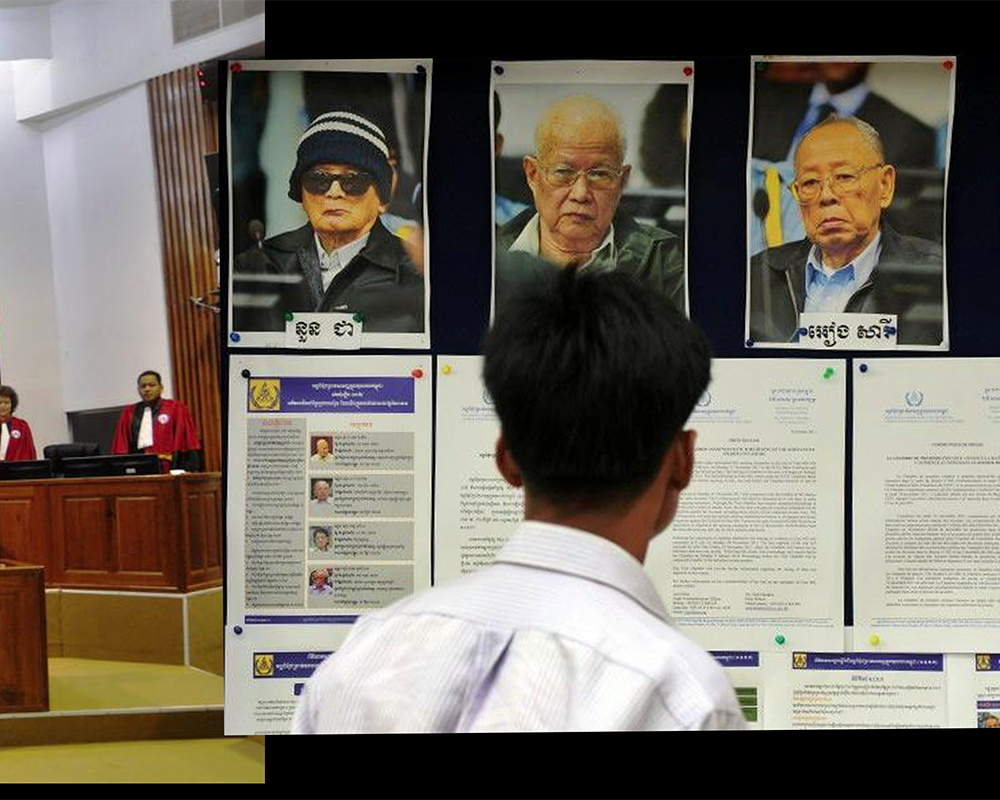

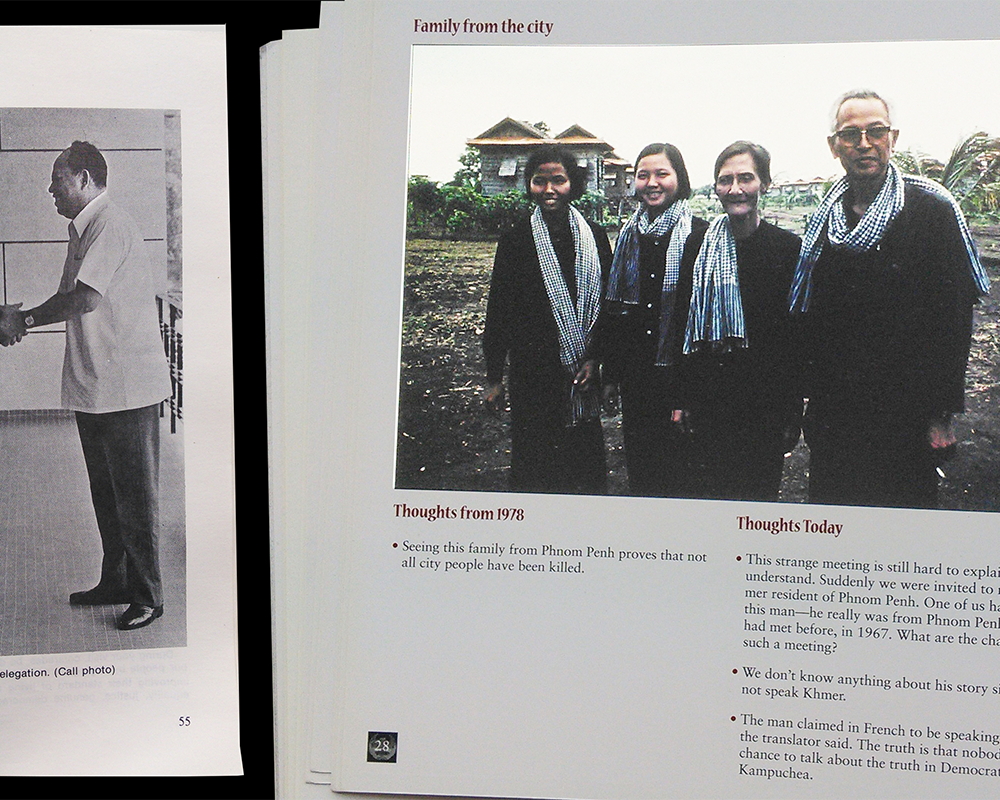

The tools I devised were tried out in different contexts:

- the photos taken by the Western friends of the Pol Pot regime while they were touring Democratic Kampuchea in 1978;

- the photos taken by the Western friends of the Pol Pot regime while they were touring Democratic Kampuchea in 1978;

- the drawings created by Cambodian children in refugee camps on the Thai border in the Eighties and their impact on the later formation of artistic scenes in Cambodia;

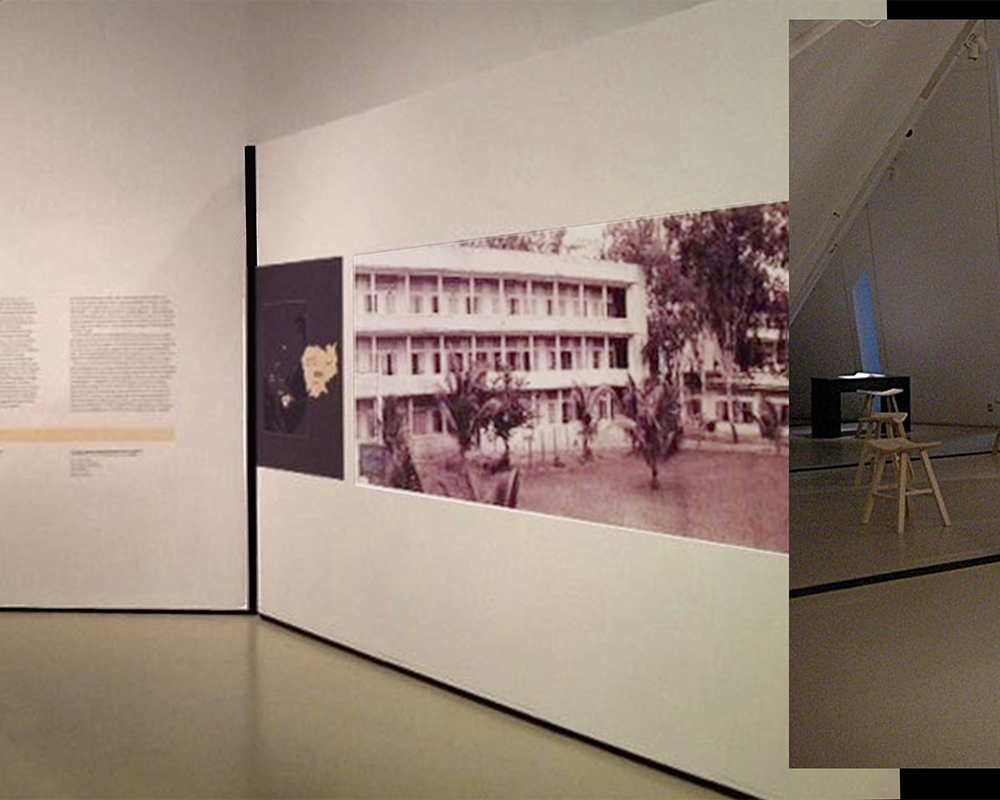

- the migration of the photos of S-21 prisoners into a widening circle of international museums and exhibitions from the late Nineties onward;

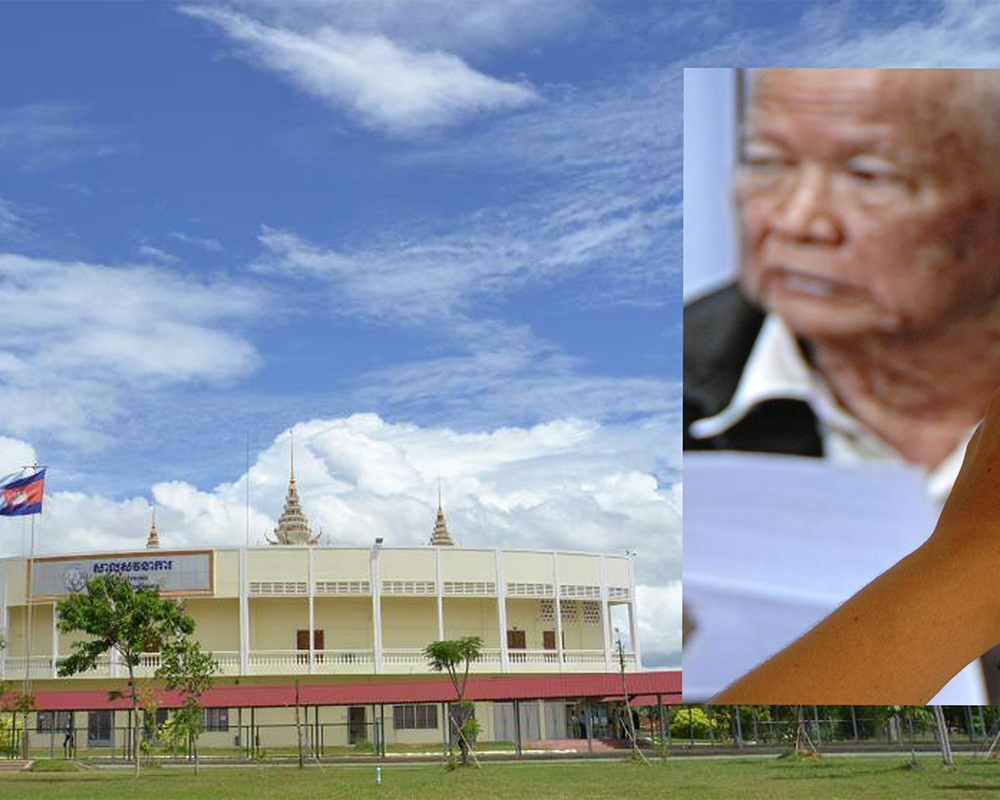

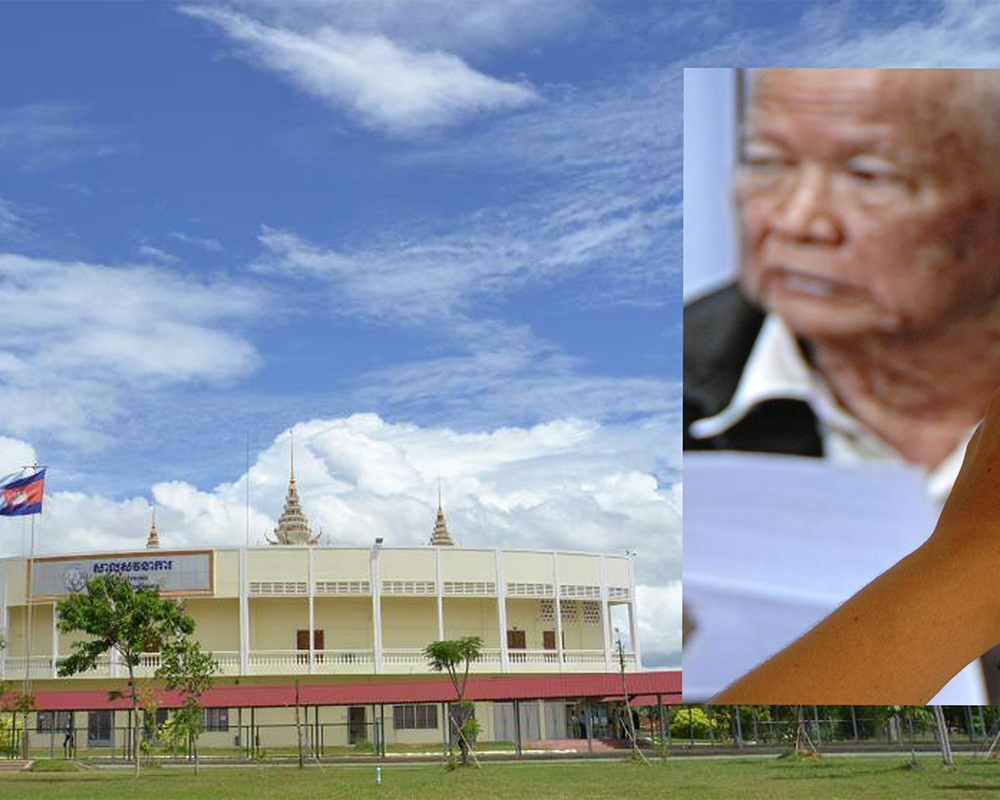

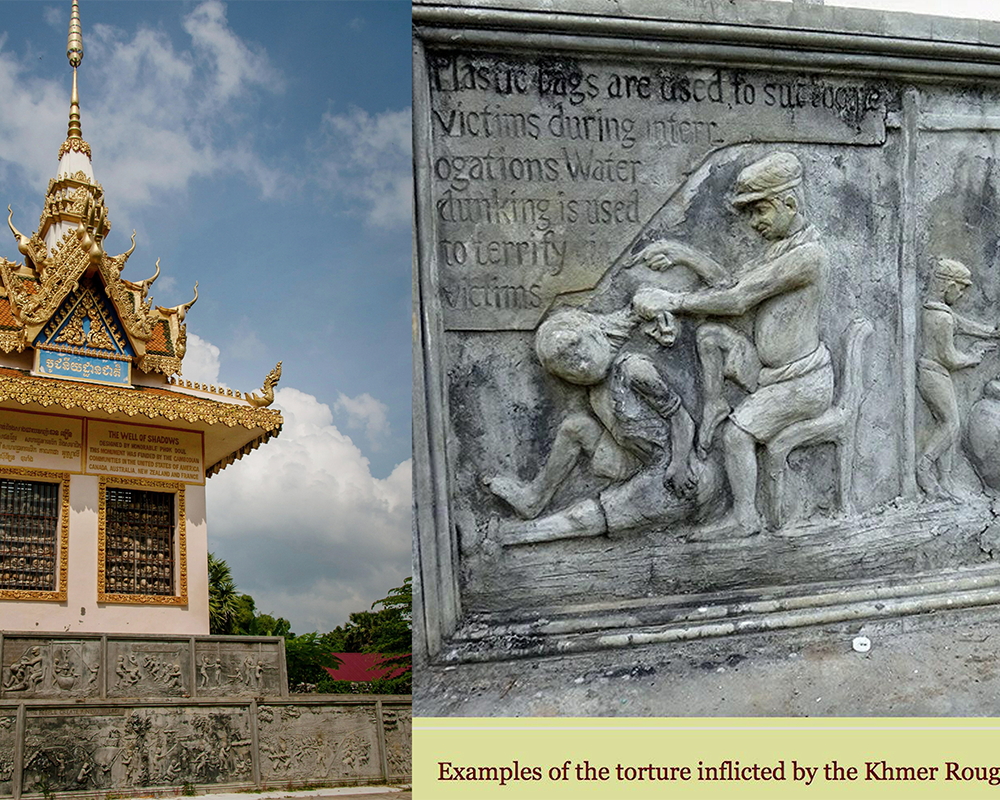

- last, the effect of the Khmer Rouge Tribunal on collective memory and public space in Cambodia through the construction of memorials, with a focus on the work of French-Cambodian artist Sera.

[10] By choosing a chronological structure for my study, my aim was to create a panorama showing the different elements that shaped over time ways of representing and seeing Khmer Rouge atrocities, among them:

- the end of the Cold War and the rise of the human rights discourse; - the changing interpretation of the notions of colonial, post-colonial, and neo-colonial;

- the constantly evolving condition of remembrance in the age of mass-communication technologies and globalized spectatorship.

So doing, I hoped to achieve what Helen Jarvis, one of the leading experts on Cambodia, once described as going beyond reductionist images of Khmer Rouge terror, in order to reach a better understanding of what happened in Democratic Kampuchea in the Seventies.

I would like to add that such an understanding is not only about Cambodia and about looking at the past, but it reflects on other parts of the world, giving us a tool to act - better equiped - now and in the future.